At long last, a certain dream of mine for almost four years now has come true—namely, for Group TAC’s long-forgotten classic film The 11 Cats, which was originally released on this very day 40 years ago, to receive English subtitles! Even better, the film is now available for viewing in a better-quality version that was previously online, and best of all, it even comes with English-subtitled versions of director Shirō Fujimoto’s three best episodes for TAC’s legendary anthology series, Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi, which showcase his unique talent as an illustrator and even painter in his own right.

Download these films directly from Google Drive!

Had I been told back in the late summer of 2016 that I, and two other friends I’ve made since then (Meizhan and Kenji, the latter of whom contributed a guest article to this very blog last year), would ultimately be the ones to undertake this project, I would not have believed it. Yet so much has changed since then, and I like to think I’ve grown immensely as a person and writer, so here we are…

Ben Ettinger has already written a nice primer on The 11 Cats and the creative figures behind it, so for this article, I would like to delve even further into the historical context behind the film’s making and what said creative figures were up to at the time, as well as offer certain insights on the film and the MNMB episodes—and Fujimoto’s own directorial vision, for that matter—that have hitherto not been brought up in a public space. Additionally, I would like to recount the tumultuous events that led up to this very day, including a look at the enormous difficulties I encountered in creating at least a semi-restored version of the film.

On the cruelty of society

To begin with, it must be stressed that working on Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi was not typically the creatively-satisfying experience that the series’s best episodes may seem to convey, especially not in its earliest years from 1975 to late 1978 when Tsuneo Maeda, an ex-Mushi Pro animator who had been launched to prominence as the lead animator of Belladonna of Sadness under Gisaburō Sugii’s tutelage, served as the series’ chief director. Although a talented animator in his own right, he did not intend the series to be a showcase for other artists’ unique styles, but instead sought a down-to-earth, alternatively cartoonish (albeit rather inoffensively so) and painterly aesthetic and atmosphere that he felt would be suited to the folktales.

Under this pretext, many of the more interesting and oddball creators involved with the series in its earliest months were quickly edged out, including such big names as Osamu Dezaki1 and Rintarō, as well as ex-Fight da!! Pyuta stalwarts Hiroyoshi Mitsunobu, Eisuke Kondō, and Tameo Kohanawa (and the animators at their new studio Tsuchida Production) and even the crazed veteran animator Daizō Takeuchi.2 A few other distinctive artists whose initial episodes on the series had been stellar, like Group TAC’s own Takao Kodama and Tadahiko Horiguchi, did continue working on the series, but their episodes were more often than not significantly toned down from what they had hitherto proven themselves capable of; the same could be said for the four episodes that Yoshiaki Kawajiri created from January to August 1978,3 towards the very end of Maeda’s time on the series. Unsurprisingly, the most interesting episodes of the series during this era were generally those that Maeda himself directed from storyboards mailed in by Sugii, who was wandering Japan at this time; in addition to the seeds of Sugii’s later pensive style being laid in these episodes, they often benefited from deft animation by Teruto Kamiguchi (which, incidentally, was itself toned down from the earliest episodes with his involvement in 1975) and gorgeous eye-candy art direction by Mihoko Magōri.

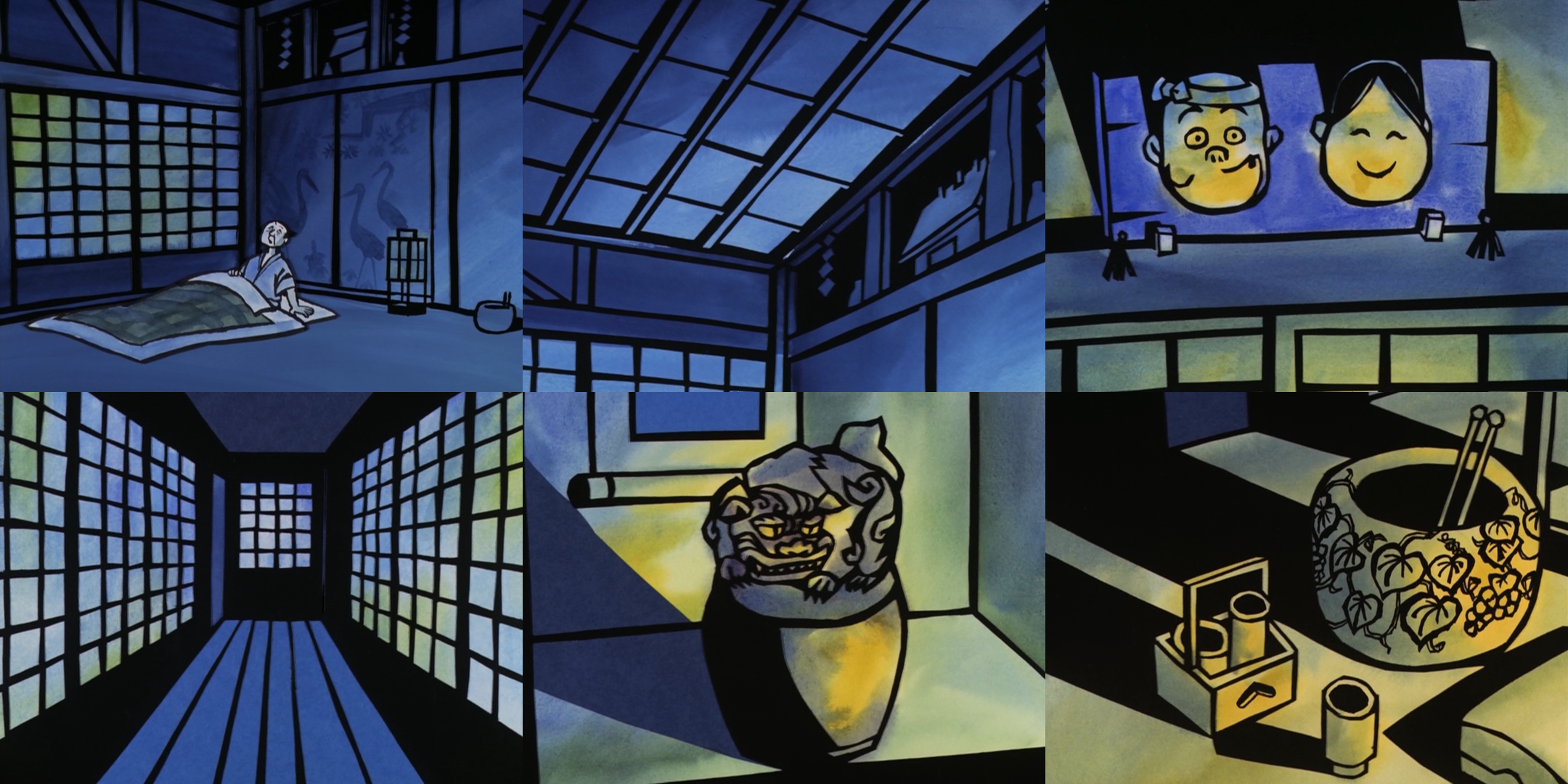

From MNMB #108 (大歳の火, The Fire of New Year’s Eve), an early masterpiece of quiet nighttime atmosphere written and storyboarded by Gisaburō Sugii, animated by Teruto Kamiguchi, and inked in a folk art style (presumably using fudepens).

Shirō Fujimoto (usually credited as “Shirō Marufu” in his earlier episodes), an ex-Mushi Pro art director whose true passion was in painting, was perhaps the other main director on the series at the time whose temperament was well-suited to Maeda’s vision. In most of his episodes, the character designs were pleasantly stylized, often cartoonish or semi-realistic without ever verging to one extreme or the other; and his atmospheric direction (which grew more bucolic as the series progressed) could alternatively be compelling or relaxed according to the needs of the story, often intricately depicting society and village life with a keen eye indicative of his own proclivities as a painter. Essentially, for the most part, Fujimoto’s episodes for MNMB are the show’s base aesthetic at its finest.

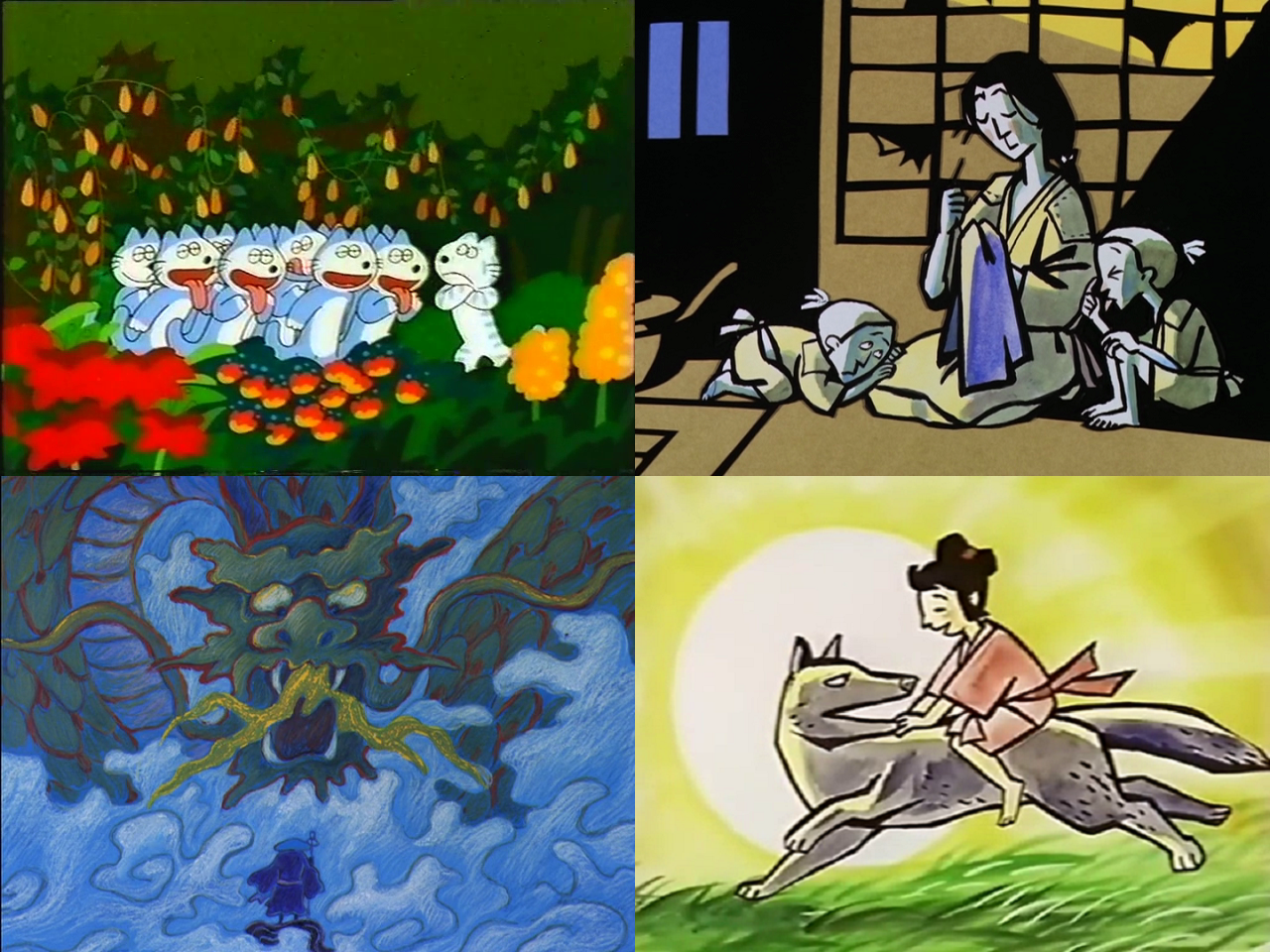

However, in the latter half of 1976, Fujimoto produced three episodes which differ significantly from the rest of his work on MNMB, and indeed may be among his finest works as a director. These episodes represent the purest expression of Fujimoto’s vision in that they are based entirely on visual storytelling through haunting, evocative paintings and cinematography with only minimal animation, brought to life in turn by Group TAC president Atsumi Tashiro’s magnificent audio direction which brings the visuals Fujio Tokita’s and Etsuko Ichihara’s charismatic narration, Jun Kitahara’s eclectic music tracks, and evocative sound design by Ishida Sound Pro (now known as Fizz Sound Creation). They are moreover the most powerful examples of how Fujimoto, more than any of the other regular directors on the series at the time, placed an emphasis on highlighting societal ills and injustices that, in spite of how much time has passed since the folktales originally took place, remain serious issues even today: all three of them tell stories of poor, innocent folks who, through no real fault of their own, find themselves rejected and reviled as outcasts by society at large.

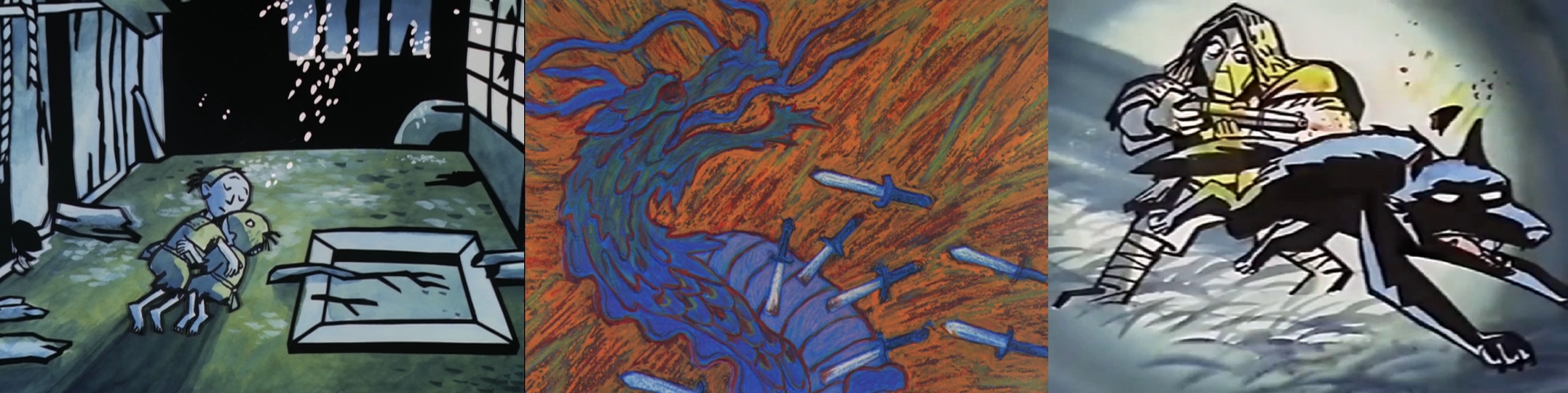

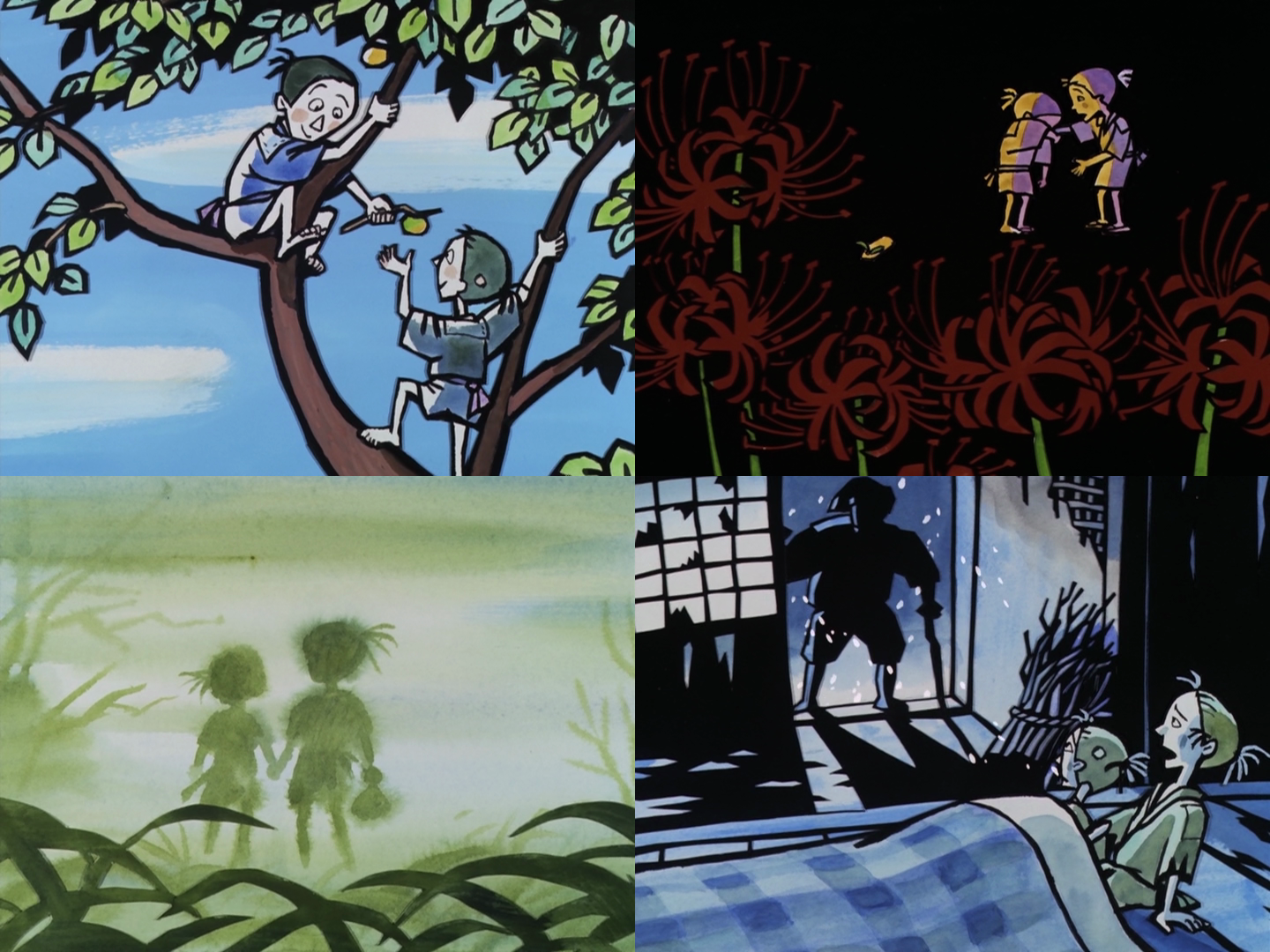

#70, The Story of the Futon (based on The Story of the Futon of Tottori, anthologized in Lafcadio Hearn’s Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan), was first aired on 24 July 1976, and is comprised entirely of beautiful art painted by Fujimoto himself. It is a heartbreaking tale that depicts the disregard and even contempt that society has for two poor boys who, after the deaths of their parents, ultimately have nowhere to turn but death, their only consolation being how they tease each other for feeling cold as they freeze in the bitter winter; their spirits proceed to haunt a futon, taken away from them by the wicked landlord who threw them out of their home, which is ultimately passed down to an innkeeper who, in spite of being poor himself and having to obtain all his supplies from second-hand shops, wishes to establish a reputable inn. The innkeeper understandably does not believe it at first when his first guest, a traveling merchant, discovers the futon is haunted and storms out; once he finds out for himself, however, he does not simply throw the futon out, but, in a move that eventually demonstrates his good-hearted, empathetic nature, starts asking around at the second-hand shops that had previously possessed the futon in order to discover why it speaks.

Fujimoto’s stark, angular, thickly-inked, and watercolor-painted artwork, influenced by woodblock prints, does a perfect job of conveying the story in tandem with the excellent soundtrack, far more so than if it had been conventionally animated like many other MNMB episodes. As director, he often lingers on each shot for an extended period of time, allowing the viewer to truly take in the atmospheric paintings and the sad events contained therein: many scenes are painted almost entirely in wintry hues of blue and brown, with shades of yellow being used to get across the brilliant, dramatic lighting in the scenes at the inn; the flashbacks to the somewhat happier life the boys lived before the deaths of their parents, meanwhile, are fittingly painted in more colorful palettes. The use of bold, stylized shadows and silhouettes is particularly important to the bleak, heavy atmosphere; Fujimoto clearly has no qualms about pushing the tragic, cold-hearted cruelty and darkness of this world, and how the poorest and most vulnerable in society will always suffer the worst from them, to the forefront by way of his striking artistry.

One of the most cinematic sequences in MNMB #70 is when the first guest at the inn gradually realizes that the futon is haunted. Here, Fujimoto cuts between several different locations in the seemingly-tranquil room, and even to the hallway outside of it, as the futon’s voices begin to pipe up amidst the silence, a great way of emphasizing the guest’s bewilderment and unsettlement over where the voices could possibly be emanating from.

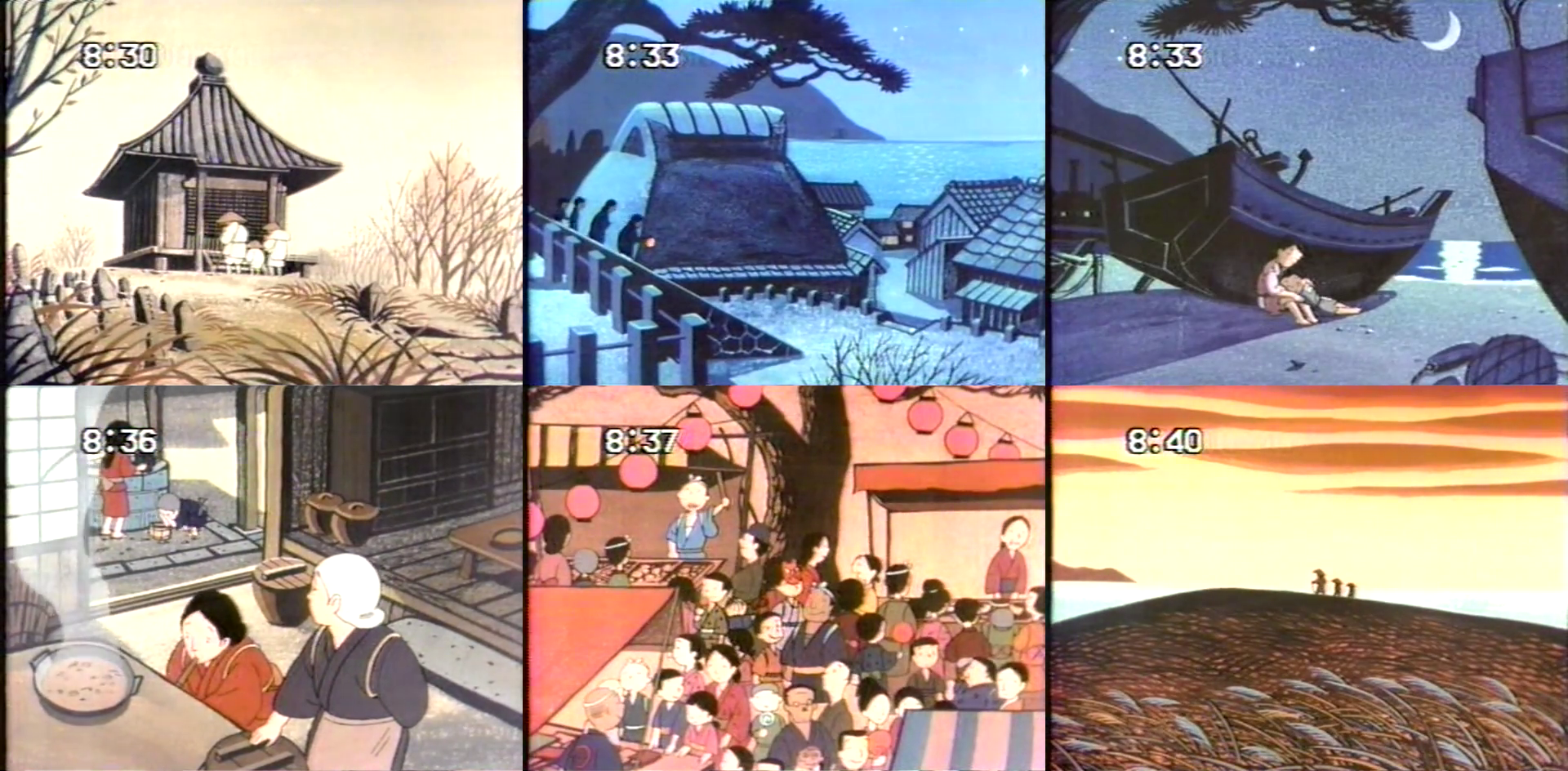

Months later on 6 November 1976 came #93, Hachirō of Hachirō Lagoon (based on a classic origin tale from Akita Prefecture), which Fujimoto used as a showcase for the talents of background artist Kōji Abe; this was the first of a handful of segments that were based entirely around Abe’s art, and it is easily the most powerful. Abe was another ex-Mushi Pro artist whose career went back at least to Kimba the White Lion; he would go on to be a mainstay of Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi for its entire run, serving at least as art director on some 91 segments.

Here, Fujimoto and Abe explore how selfishness, and the needless, arbitrary, even absurd persecution it often leads to, can turn even the most kind-hearted people into embittered, unfeeling monsters simply for denying them what they need: Hachirō is an innocent young lad who, in a twisted and disproportionate punishment perhaps intended as a learning experience, is transformed into a giant dragon simply for succumbing to his friends’ shares of some delicious char fish in the mountains, in turn getting tormented so ruthlessly by humans (in particular a powerful monk who brutally drives him out of Towada Lake), dogs, and gods alike in his search for a home with abundant water that he eventually loses the lingering humanity in his heart and, unable to feel remorse any longer, calls forth storms to create a huge, deadly flood in order to quench his thirst. Only when he at last finds himself gazing out on a lonely, uninhabited land does he suddenly remember his human past, and begin to cry once more; at that moment, as though symbolizing the breaking of a new dawn for him, the sound of a rooster finally gives him the resolve to turn this land into his permanent home, unimpeded by any persecutors—at the same time, however, he has regained his former kind-hearted self, saving an old couple from drowning as he brings Hachirō Lagoon into existence.

Kōji Abe’s artwork is an impressive contrast to Fujimoto’s own work in the previous episode. Whereas Fujimoto’s woodblock-inspired art is characterized by firm, rigid forms and solid linework and generally sparse palettes rendered with watercolor washes, Abe’s art here goes in a more overtly theatrical and passionate, at times even grotesque direction, crafting all the visuals—figures and settings alike—in chaotic, uneven, sinuous lines and decadent, sketched-out and brushed textures with extravagant amounts of detail and rich, multi-colored palettes (Hachirō is especially well-drawn in his dragon form); the main comparison that comes to mind is the art of Vincent van Gogh. This expressiveness perfectly reflects the intensely distorted way that a winding dragon—or even an innocent simpleton like Hachirō used to be—would undoubtedly see the world; it seems likely that Fujimoto himself, having already laid out the episode’s brilliant compositions in his storyboard, pushed for this unique aesthetic, as Abe would never create anything like this again, not even in his own art-based episodes.

Incidentally, it is mentioned at the very end of the episode that Hachirō later married Princess Tatsuko of Tazawa Lake, whose own story—in a way, she was the Japanese equivalent of Narcissus—would be adapted years later in an even more beautiful art-based episode, #626 (辰子姫物語, The Tale of Princess Tatsuko), aired 14 May 1983. It was written and directed by Gisaburō Sugii with art by his close collaborator Mihoko Magōri, and is easily my favorite of the art-based episodes they did together.

Finally, on 11 December 1976 came #100, The Wolves and the Girl, which is a stellar encore of Fujimoto’s own art as previously seen in #70; for a change, Fujimoto himself wrote the adaptation, with series mainstay Isao Okishima (who had been the screenwriter of the previous two episodes) being relegated to his usual role of re-writing the dialogue to match the dialect of the region the story takes place in. This time, Fujimoto illustrates an even more dramatic story about a mother and her daughter who, having been reduced to poverty and a life of endless pilgrimage by their swindling relatives after the father’s death, wander into a village that forbids the sheltering of outsiders; their only comfort comes from an old woman who, although unable to let them stay for the night, gives them food and advises them to ask for shelter at the nearby Ryuuunji Temple. Unfortunately, the head priest there proves to be the most heartless of them all, forcing them to sleep underneath the temple with the expectation that they will be slaughtered by the wolves later that night; there, the daughter wonders what has happened to her wolf cub Gorō, who was taken away to be killed after he grew too big, but escaped. In what seems at first to be a cruelly ironic twist (and a truly frightening and well-directed sequence in itself, depicted at times from the characters’ own points of view), the head priest is the one who is eventually killed and eaten by a pack of wolves; it soon turns out that Gorō is their leader, and that he has reunited with the daughter. When the wolf pack attempts to attack the village itself out of similar vengeance one day, the daughter runs in and pleads with Gorō to stop, remembering how there was at least the one old woman who had helped her and her mother—and is accidentally shot and killed in the process. It is only this tragic incident that finally convinces the villagers as a whole to end their hostility towards outsiders; the wolves themselves turn to stone as they mourn the death of the young girl, but it is said that their lamenting howl can be heard on moonlit nights to this day. (“A compelling tale of karma and retribution,” as Ben Ettinger aptly put it…)

Fujimoto continued to direct more conventionally-crafted episodes for MNMB even as these were being made, and he would continue to direct many more episodes for the series all the way up to the end of August 1978, including some with similar social themes; even from an artistic standpoint, however, none of them would ever again be quite as radical as this trio. Perhaps chief director Maeda did not want Fujimoto to do any more painting-based episodes, only accepting these ones in particular because they worked so well with the subject matter, or Fujimoto himself knew he had to give work for the animators themselves to do; in any case, one is left wishing that Fujimoto had been able to show his talent as a painter more often in the series.

Children’s literature: dangerous ally for the animation film-maker?

While Tsuneo Maeda’s approach as chief director on Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi may not have been ideal from a creative standpoint, the series nevertheless proved to be an enormous hit among audiences (and deservedly so), ultimately becoming a cultural mainstay fondly remembered by many Japanese of a certain age; its continuous run of nearly 20 years, superseded in TV anime only by a handful of other shows, was no doubt beyond what anyone at Group TAC at the time was expecting. Indeed, such was its success that the Mainichi Broadcasting System, the series’s co-producer and main broadcaster, decided to commission two further series from Group TAC with a similar format as MNMB: Manga Ijin Monogatari and Manga Kodomo Bunko.

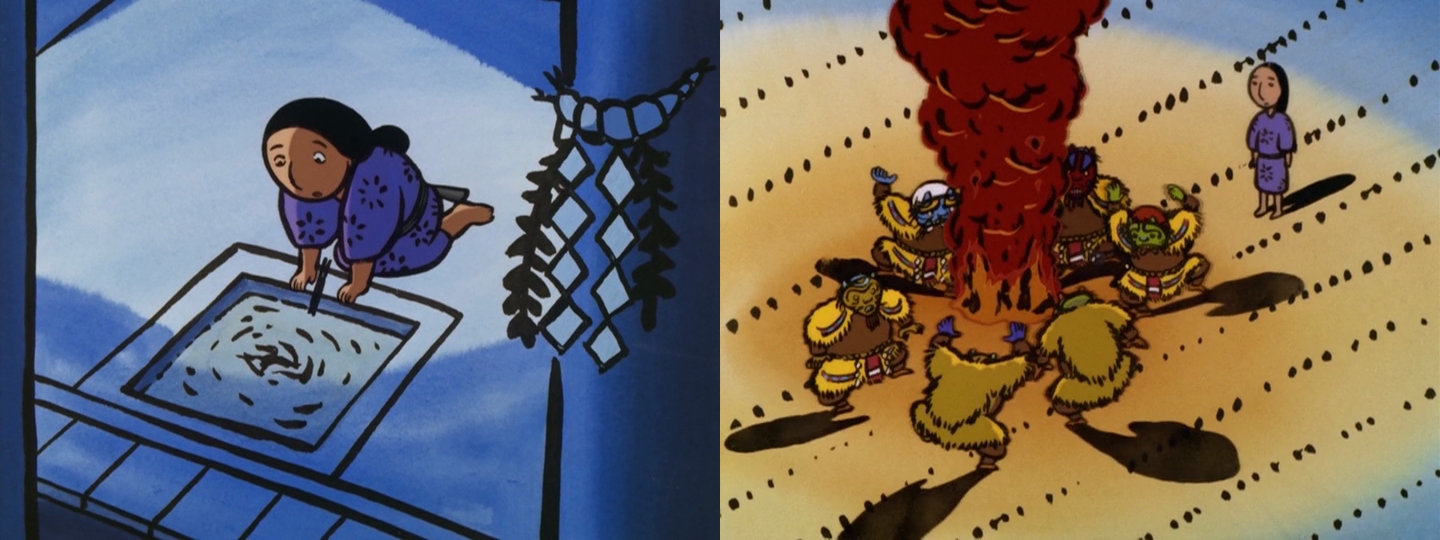

It is Manga Kodomo Bunko, aired from 6 October 1978 to 28 September 1979, which is most pertinent for the purposes of this article. To begin with, not only Maeda, as chief director, but also Shirō Fujimoto and animator Teruto Kamiguchi, and for that matter a few others like Norio Yazawa who had been mainstays of MNMB (Yazawa was in fact the animator of Fujimoto’s final MNMB episode, the haunting #237 (マヨヒガ, Mayohiga), aired 26 August 1978), migrated over full-time to this new series. Moreover, Fujimoto appears to have played an even more important role here than on MNMB: in addition to regularly directing, he received a credit for the series’s composition at the beginning of every half-hour, indicating he may have been responsible at least in part for its very concept and structure (for the majority of the series’s run he was strangely credited for this role alongside Masakazu Higuchi, who denied that he himself played any role in this regard). Most crucially, the series, which brought to life classic Japanese children’s literature and songs4 and relied greatly on its sumptuous art direction in that respect, proved to be Fujimoto’s penultimate involvement in animation, and may well have even provided the initial impetus for his decision to quit the industry altogether.

It is unfortunate that less than half of this series has been preserved for viewing online, as the few Fujimoto-directed episodes that are available are, in general, the ultimate expression of the atmospheric, painterly, and detailed direction—coupled, at times, with gritty social commentary—that characterized his later MNMB episodes; easily my personal favorite in this regard is his very first segment for the series, #1B (まつりご, The Festival Kimono), about two long-suffering orphans who get adopted by a temple. The unavailability of the majority of the episodes is even more regrettable in Kamiguchi’s case: the only surviving evidence of his involvement with the series is #38A (三太物語 三太花荻先生と野球, Santa’s Adventures: Baseball With Ms. Hanaogi), directed by Tsuchida Pro’s Hiroyoshi Mitsunobu, and it is a great example of his knack for creating natural-looking character animation through excellent posing, lively motion (his characters, whenever they move around, very often do so on twos), precise modulation (they even shift to ones where it is particularly effective), and just the right amount of well-timed gestures and little movements even in otherwise-static dialogue scenes. To top this all off, one viewer of the series who recorded a number of episodes at the time has even stated that there was at least one episode in which, just as they had on MNMB and would soon do again on The 11 Cats, Fujimoto and Kamiguchi collaborated: #15B (赤いもち白いもち, Red Mochi, White Mochi).

Scenes from Fujimoto’s first episode for Group TAC’s short-lived Manga Kodomo Bunko. The gorgeous background art was painted by Kazunori Shimomichi.

As the autumn of 1979 approached and Manga Kodomo Bunko was wrapping up, Gisaburō Sugii briefly returned to Group TAC from wandering to direct three episodes of Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi (#323 きつねの嫁取り, #335 一軒屋の婆, and #338 岩屋の娘), and for a very short time Kamiguchi and Tsuneo Maeda returned to MNMB to work under Sugii on these episodes. These were the masterworks that exemplified both how multifaceted Sugii was as a director and how his filmmaking approach had evolved in his years of wandering: each of them approach the subject of kitsune from different viewpoints (both thematically and visually), and in each of them Sugii utilizes his pensive mode of direction for decidedly different—yet equally brilliant—ends. To discuss them in-depth now would unfortunately be beyond the scope of this article; but, I hope to return to this fascinating kitsune trilogy, as it were, at a later date… (Kamiguchi also animated one other MNMB episode around this time, #328 (御船川, The Mifune River), directed by Tsuchida Pro’s Eisuke Kondō—and featuring backgrounds by Minoru Aoki, with whom Kamiguchi would soon work on an even larger scale…)

Fujimoto, on the other hand, never returned to MNMB after the end of Manga Kodomo Bunko. He may well have already begun pre-production work on what was, perhaps, destined to be the swan song of his animation career.

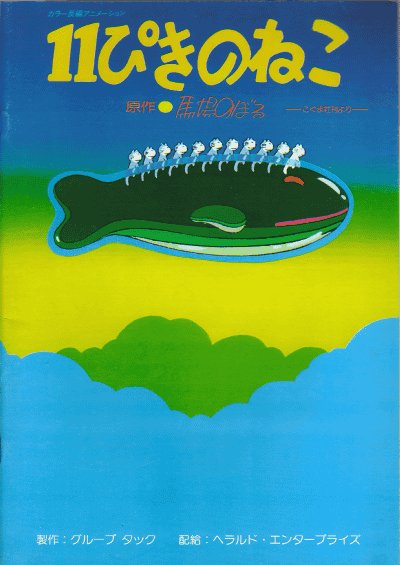

The 11 Cats, based on Noboru Baba’s popular 1967 picture book of the same name (translated outside Japan as Eleven Hungry Cats), was Group TAC’s second feature film. Notably, it was the studio’s very first project to credit Tsuneo Maeda as “animation kantoku” (アニメーション監督), a role he would go on to play in several of the studio’s most important projects afterwards. It is perhaps best translated as “animation supervisor”, as it was a role altogether different from the “sakuga kantoku” (作画監督) which is usually translated as “animation director” (and whose role in Japanese animation, generally speaking, is to keep the animation up to a certain standard of quality, not least by correcting other animators’ drawings so as to keep them “on-model”); according to Sugii and animator Marisuke Eguchi, the latter of whom’s earliest known on-screen credit is on this film, Maeda’s role in this capacity was essentially to serve as a technical director, overseeing the technical aspects of the animation and deciding what would be needed to actually pull off any distinctive visual concept it had. Art director Minoru Aoki’s backgrounds were notably painted on cels like the characters themselves, creating a unified flat, colorful picture-book aesthetic—the task of actually painting them was handled by cel painters at a certain young studio named SHAFT.

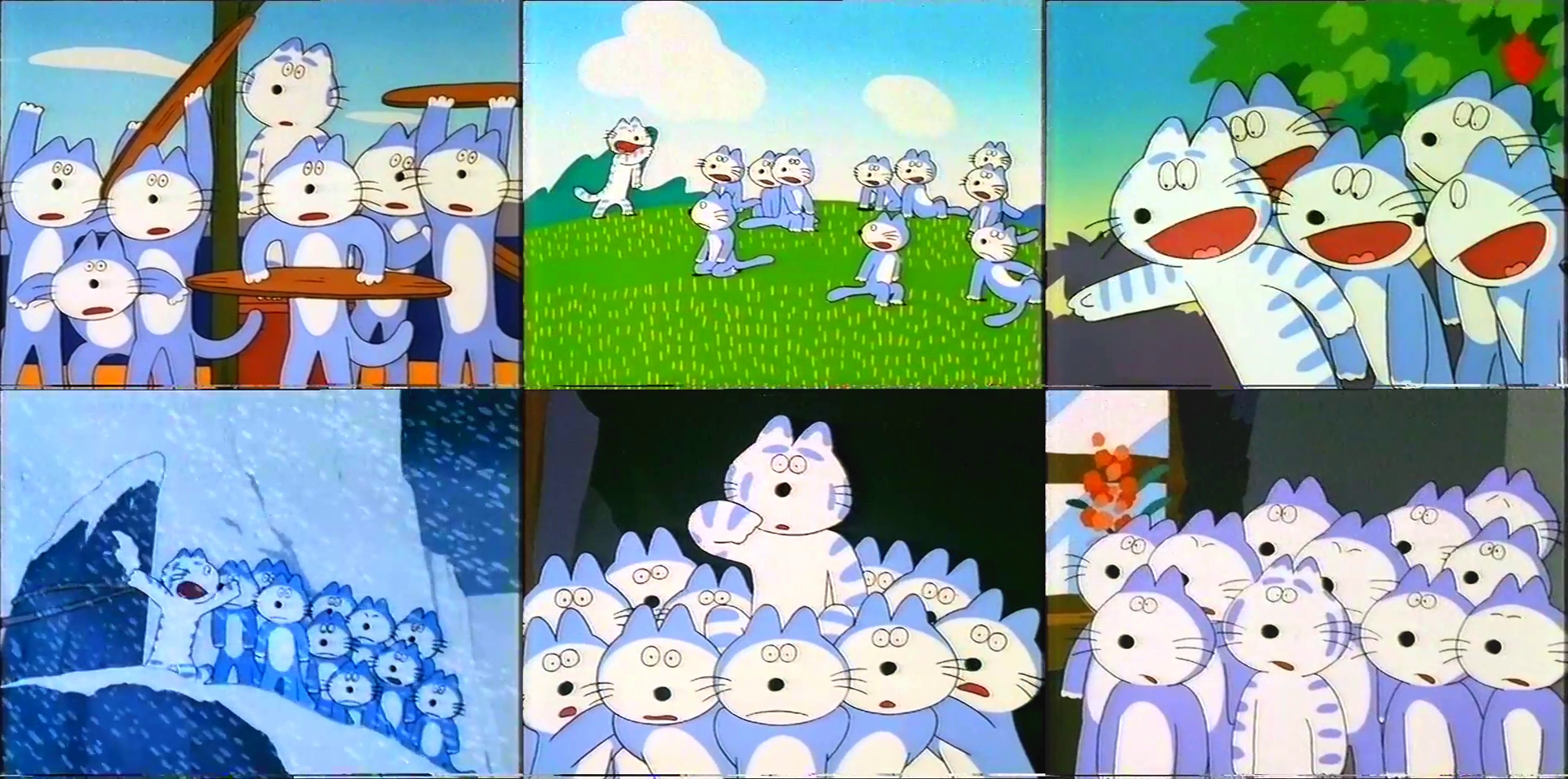

The original book on which the film was based was, as Jiří Brdečka would say, a literary soufflé; it simply introduces the 11 Cats as hungry strays dividing a small fish between themselves followed by their encounter with the old cat who tells them about the big fish in the lake beyond the mountains, with most of the book in turn being occupied by their attempts to catch the big fish afterwards. In expanding such a barebones affair into a compelling feature cartoon, Fujimoto relied not only on chief animator Teruto Kamiguchi to imbue the cats with the flair and personality necessary to bring them to life entertainingly, but also on the film’s brilliant voice cast—led, in a classic example of Atsumi Tashiro’s willingness as producer and audio director to try unusual things, by then-famous singer Hiromi Gō as the 11 Cats’ leader Commander Tabby—and for that matter on the gifted screenwriter Yoshitake Suzuki, who turned the story into an epic journey with plenty of laughs, some valuable lessons about the importance of friendship, a number of tears, and (as Kenji pointed out) even a few allusions to Homer’s prototypical Odyssey along the way: the lush oasis at which the cats feed on silver vine (resulting in a stellar psychedelic interlude) and find themselves unwilling to leave is strikingly reminiscent of the island of Aeaea where Circe resided and drugged Odysseus’s men (who, even after being changed back from swine, proceeded to stay for a year), the one cat tied to the mast on their raft as they scout out the big fish is similar to how Odysseus himself was tied up there so that he could hear the sirens’ song, and in that regard even the big fish’s lullaby—which in the original book had no effect on the cats beyond tricking them into thinking it was letting its guard down, albeit the crucial twist of them eventually turning the lullaby against the fish was certainly present—is turned into a deadly siren song in its own right, explicitly intended to lure the cats to sleep so that the fish can eat them all up.

Suzuki, who is largely known for his screenwriting work on various classic mecha/sci-fi anime under the pseudonym Fuyunori Gobu, was almost certainly educated enough that he knew what he was doing with these allusions to the Odyssey. He had already served as the head writer of the legendarily satiric gag comedies Goku’s Big Adventure and Fight da!! Pyuta in the late 1960s and then of Mushi Pro’s Andersen Monogatari (adapting tales by Hans Christian Andersen) in 1971, and just years earlier he had even written some segments for Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi and Manga Ijin Monogatari, so it seems obvious he had a solid grounding in history and literature. In any case, what makes these allusions fun in The 11 Cats is that, as Meizhan succinctly observed, “every piece it took from the Odyssey was warped to have the stupidest motivation and execution possible.”

Fujimoto’s own worldview, as previously delineated in his best Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi and Manga Kodomo Bunko episodes, comes through strongly in the extensive exposition that sets up the cats’ journey. The film depicts a civilized cat society not unlike that of humans, complete with all the feline villagers living in quaint towns across the land, typically wearing clothes of some kind, and essentially behaving as though they were just humans in cat costumes with their own unique societal roles to play, and in this respect the 11 Cats’ identity as free-roaming strays—who, on top of this, are naked and behave more like actual cats than the purely anthropomorphized villagers—serves to stigmatize them as outcasts; their inability to assimilate means that their only way of getting food to live is to run around town as a group—chasing mice around, foraging, taking whatever is on the ground—all of which inadvertently but regularly disrupts the established social order, causing chaos and misfortune throughout the town.

Indeed, the opening episode in the original book, in which the 11 Cats equally divide a small fish on the road between themselves, becomes the final straw in the film. Here, the fish turns out to have been accidentally dropped by the fishmonger, who had already gotten the worst of it from the cats earlier that day, while he was transporting his catch to the market. Summoned by the angry police chief, the cats are rebuked and told that strays are an inconvenience for everyone: from this point on, they must end their way of life for the benefit of society as it already exists, or be forcibly disbanded.

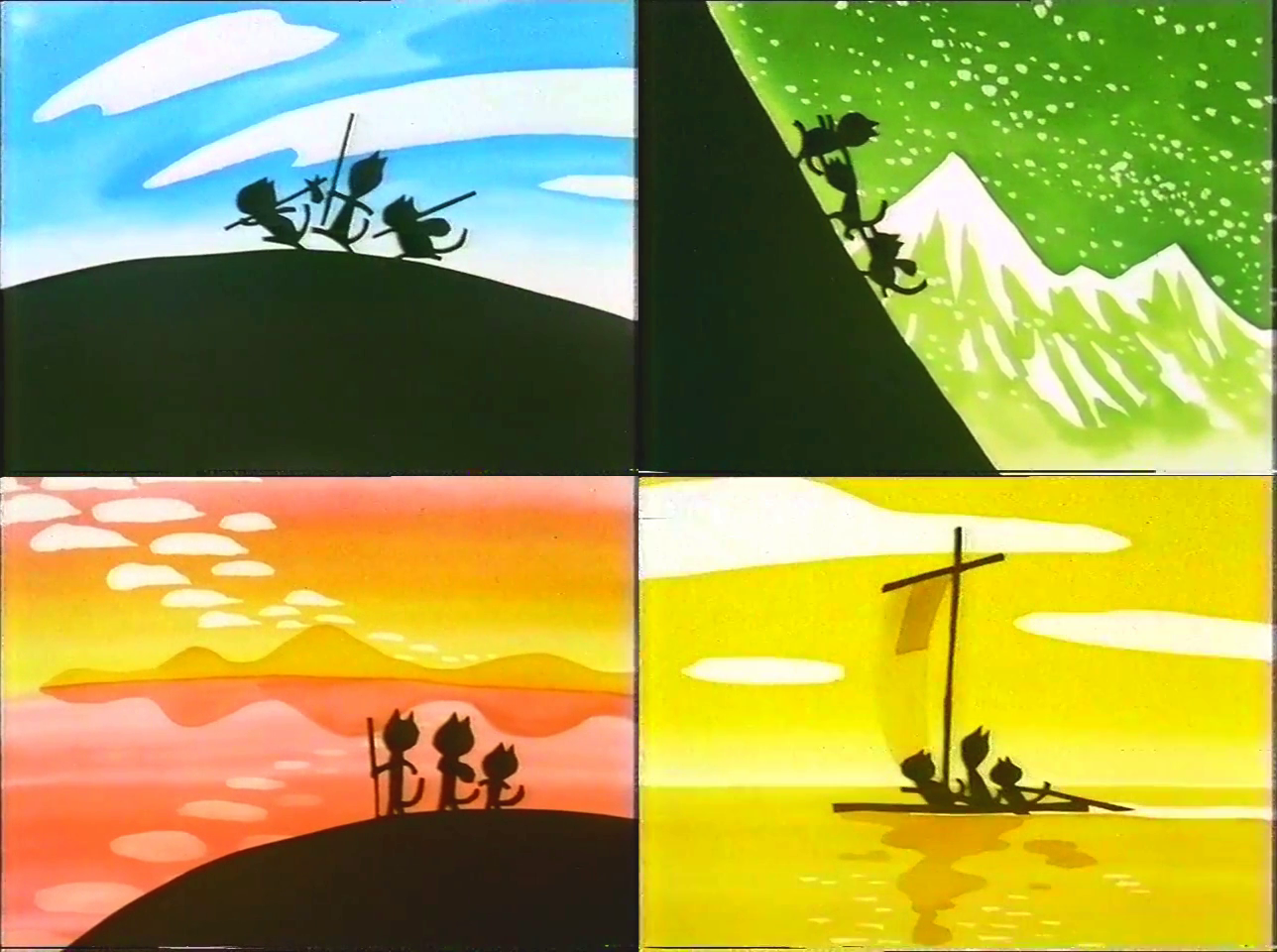

The old cat whom the 11 Cats meet, named Old Man Longwhiskers in the film (and voiced by Ryūji Saikachi), is himself depicted as a vagrant drunk hated by the entire town, even most of the 11 Cats themselves; only when he discusses the big fish on the other side of the mountain at their leader Commander Tabby’s request, under the pretense that capturing it would be a good way for the 11 Cats to prove themselves real cats (and not, as had been the case in the original book, out of any altruistic desire to alleviate their hunger), do they rather cynically begin paying any serious attention to him. It is here that Fujimoto’s experience as a director on Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi is most plainly evident, as the old man’s knowledge regarding the big fish is expanded into an entire folktale about three cats who, like Longwhiskers and the 11 Cats, were despised by their village, and in turn set off on an adventure, with the big fish being given downright legendary status as a monster the three cats could not defeat; Fujimoto even illustrates the story using stylized, silhouetted watercolor paintings (pictured above) that look almost exactly like the artwork in the MNMB episodes he had crafted himself, effectively making the sequence a continuation of those episodes both visually and thematically. In this sense, The 11 Cats works brilliantly as a feature-length extension of both Manga Kodomo Bunko and Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi; even aside from the film’s key artists contributing significantly to both shows, it manages to adapt a classic Japanese children’s book (albeit a much more modern one than those featured in MKB) in a manner unique to its artists while expressing a fascination with folklore and mythology and how, even in the present day, they can communicate timeless themes and observations on life—and all while not taking itself too seriously, to boot.

These significant additions to the prologue—and for that matter the numerous trials the 11 Cats must overcome between their meeting with Longwhiskers and their arrival at the lake, all of which were newly-conceived by Suzuki and Fujimoto for the film, in which the cats realize that they cannot live without each other and that even the most vivid dream is only a dream until they themselves work together to make it come true—ultimately give more weight to the 11 Cats’ decision towards the end of the story, after they have defeated the big fish, to try and show the other cats what they have done instead of eating the fish immediately. In the book, the decision was made by Commander Tabby out of simple vanity; in the film, however, they are convinced to bring it back to town by one of the pluckier cats (voiced by Hiroko Maruyama) precisely as a way of showing the numerous villagers and officials who had hated them and their relationship, made fun of them, underestimated them, looked down on them and their unwavering belief that the big fish existed—not only in their own town, as a matter of fact, but also in other towns they had passed by on their journey—that they were wrong. The story, in the end, is transformed into an ode to rebellion against the misguided assumptions and hostility that society will bear against you just for being who you are, not to mention an ode to the power of camaraderie and how friends can accomplish so much more together than individually—even if the punchline is still that the 11 Cats end up eating the big fish anyways, leaving only the skeleton to carry home.

Incidentally, then-Group TAC mainstay Takao Kodama is credited for the film’s title design, which would seem to conflict with how the 11 Cats’ original author, Noboru Baba, is himself credited for the title illustrations. I would take this to mean that Kodama was responsible for the cute little scene at the very beginning of the film in which Commander Tabby seems to extend behind the fence pickets before the 11 Cats all jump out at once; the very motif of the blank screen zooming out on the Commander’s face would show up again in the 1983 closing for Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi, which Kodama designed and directed with animation by Teruto Kamiguchi.

Kamiguchi, as the chief animator of The 11 Cats, defined the film’s unique animation style, emphasizing simple yet movable designs over detailed drawings. In this regard, it is unlikely that he played the role of a typical “animation director” in Japanese animation and corrected any of the animators’ drawings for the sake of keeping them “on-model”: the 11 Cats can look very different depending on who is animating them in a given sequence!

The top-billed animator on the film, besides Kamiguchi himself as chief animator, was Takamitsu Yukawa, whom Ettinger already discussed quite a bit in his primer (this was the same year, in fact, that Yukawa helped out with Taku Furukawa’s Noburō Ōfuji Award-winning film Speed). Second-billed, however, is Tsuneo Wakabayashi, who like Kamiguchi was an ex-Mushi Pro animator, and indeed the two of them had even animated together on episodes 46 and 52 of Osamu Dezaki’s seminal Ashita no Joe in 1971; Wakabayashi, along with several other ex-Mushi Pro animators involved with Joe, would continue working under Dezaki on Nobody’s Boy Remi in 1977-78, but immediately afterwards he moved over to Group TAC, animating first on some Manga Kodomo Bunko episodes and then becoming one of the regular director-animators on Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi for the entirety of its run after 1979, directing and/or animating a whopping 74 segments until the series ended in 1994, and even after that animating on Shōji Kawamori’s unsung 1996 masterpiece Spring and Chaos (produced by TAC for the centennial of Kenji Miyazawa’s birth).

Two other notable animators on the film were, as Ettinger mentioned, the ex-A Production animators Hideo Kawachi and Michishiro Yamada, both of whom worked on the film from Ajia-do (the second successor studio to A Pro); they and the studio’s two main luminaries, Osamu Kobayashi and Tsutomu Shibayama, had already begun contributing significantly to TAC’s Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi by this time, and indeed even contributed a number of segments to Manga Kodomo Bunko (Ajia-do’s first involvement as a studio). Kawachi, in particular, was perhaps one of the most interesting figures to arise from A Pro; after animating on several episodes of Tokyo Movie’s seminal sports drama Star of the Giants for the entirety of its run (1968-71), he became the legendary animator Yasuo Ōtsuka’s right-hand man, serving as the de facto animation director and lead animator of those episodes of the original Lupin III series and Samurai Giants that were animated at A Pro proper (Yamada’s earliest work as a key animator, in fact, was as part of Kawachi’s unit on the latter show), as well as animating on Isao Takahata’s two Panda! Go, Panda featurettes. He would leave A Pro after the end of Osamu Dezaki’s The Adventures of Gamba—one of the episodes he worked on, 17 (about the mice taking turns serving as leader of the group, and the only episode of the series directed by Dezaki himself to be animated at A Pro besides the first one), was Dezaki’s own personal favorite from that series—to continue working under the Takahata/Hayao Miyazaki circle on 3,000 Leagues in Search of Mother and Future Boy Conan (of which Ōtsuka was once again the main animation director) at Nippon Animation, even obtaining credit as the top-billed animator on several episodes of the latter; he then joined Ajia-do, reuniting with the other ex-A Pro figures, but even then continued to have sporadic involvements with Miyazaki and Takahata, animating on Miyazaki’s Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro less than a year before The 11 Cats and even Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies in 1988. Since 1993, Kawachi has served as the chief director of the Ajia-do children’s anime Nintama Rantarō, which continues to broadcast on NHK Educational TV to this day; it holds the record of being the second longest-running TV anime of all time.

On another note, while all the animators on the film besides Kamiguchi are credited simply as “animators”, those credited from Jirō Saruyama on were almost certainly the film’s inbetweeners: not only are they noticeably listed in a separate section from the other animators, but, judging from available credits, they all seemed to devote their careers almost exclusively to inbetweening, even after 1980. Indeed, Saruyama may have already begun serving as TAC’s inbetween checker by this time, as he is specifically placed at the top of this section of the credits; he, too, was an ex-Mushi Pro animator, with inbetween credits on, among other things, the first and third Animerama films (A Thousand and One Nights in 1969 and Belladonna of Sadness in 1973).

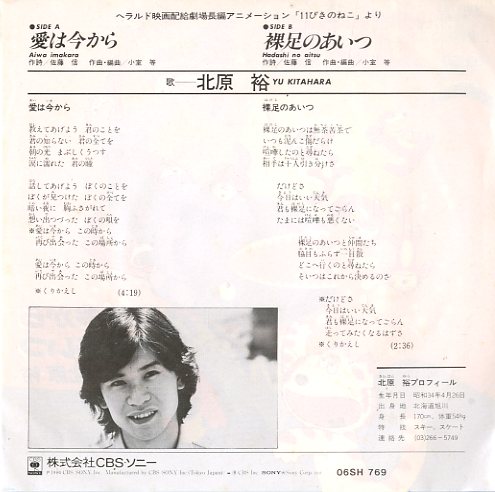

Hitoshi Komuro’s memorable score for the film, which runs the whole gamut of folk rock from playful bluegrass-inspired ditties to mellow bossa nova-influenced laments to powerful rock ballads, was performed by a star ensemble consisting of Eiryu Kou (洪栄龍) on electric guitar, Jirō Itō (伊藤次郎) on electric bass, Shigeyuki Suzuki (鈴木茂行, strangely credited here as 鈴木茂樹 or “Shigeki” Suzuki) on drums, Yumiko Watanabe (渡辺裕美子) on piano, Takahiko Ishikawa (石川鷹彦) on acoustic guitar, Masahiro Takekawa (武川雅寛) on violin, and Kōichi Matsuda (松田幸一) on harmonica; hopefully this serves as a starting point for further research into the careers of these musicians, some of whom are quite famous in their own right.5 The poetic, often poignant and at times enigmatic songs were penned by the innovative playwright Makoto Satō (佐藤信), who had been a significant part of the underground theatre (angura) movement in the 1960s and co-founded what is now known as Black Tent Theatre (劇団黒テント) in that regard, and mostly sung by then-CBS/Sony label singer Yū Kitahara (北原裕), of whom sadly nothing else is known (this song, from 1981, comes from his only known record outside of The 11 Cats‘s soundtrack).

The 11 Cats was released by Nippon Herald on 19 July 1980, as part of a double bill with a Japanese-language version of the 1979 British family film Tarka the Otter (based on a novel by Henry Williamson); this cut of Tarka, which seems to have completely disappeared into obscurity, featured a new soundtrack by Nozomi Aoki and folk musician Kōsetsu Minami, as well as animated opening and closing sequences designed and supervised by an obscure children’s manga-ka named Bonten Yumeno (夢野凡天). The leaflet advertising the double feature included words of praise for The 11 Cats from several interesting figures, not least of whom were legendary manga-kas Osamu Tezuka and Fujio Akatsuka: Tezuka offered high praise for the film, stating, “To me this work has a scale and philosophical depth even beyond [Ernest] Hemingway’s ‘The Old Man and the Sea’,” while Akatsuka, true to form as the king of gag manga, quipped that “I wish I could show this to [my cat] Kikuchiyo. Please organize a Cat-Viewing Day and take the ‘price of ad-meow-ssion’.” (The original pun was nyan-jō-ryō (ニャン場料), based on replacing the first part of nyūjō-ryō (入場料) or price of admission with the Japanese onomatopoeia for meowing.)

It seems the experience of working on Manga Kodomo Bunko and The 11 Cats made Shirō Fujimoto realize that his calling in life was to actually illustrate children’s books himself, rather than simply adapt others’ stories into animation; so, with this feature film as the ultimate statement of his worldview, Fujimoto left animation altogether. Since then, he has been quite prolific as an illustrator, and he has regularly held exhibitions of his artwork (including numerous beautiful landscape paintings); it is my hope that someone will reach out to him and interview him about his animation days while he is still alive.

Given the thought and effort that was clearly put into the film, and given that it must have been popular enough on its original release for Group TAC to have adapted the second 11 Cats book a number of years later, it seems inexplicable that The 11 Cats has received no proper home video release in Japan, not even on VHS; perhaps there are rights issues with the original book’s publisher that have prevented any such releases from happening, at least for the foreseeable future. Needless to say, this handicap was just one of many that made the very idea of translating the film into English seem farfetched; but, with enough patience and effort, anything is possible…

On a shroom’s word: reconstructing and translating the film

I first watched The 11 Cats on the night of 28 July 2016, in the midst of that idyllic and difficult yet seemingly innocent period when, as a less-than-18-year-old, I was writing my earliest pieces for this blog while digging deeper into Group TAC’s unique oeuvre as a studio. That same night, I recommended the film to an ex-bosom buddy of mine with whom I used to have several late-night conversations (this particular conversation was the same one in which I brought up the idea of an article on Kōji Nanke, my original plan being for him and I to collaborate on it); it was his love for the film, when he finally got around to watching it over a month later, that gave me hope that, perhaps, there was an audience for the film after all. I still remember one thing in particular that he said to me in a later conversation, towards the end of 2016: “I’ll make the 11 Cats popular—somehow. This is my new life’s goal.” Much later, on 13 August 2017, The 11 Cats was the first film that I groupwatched with my friend Mew, whose consistent support over the years I cannot be grateful enough for; soon enough, I was watching Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi segments with both him and a new friend, Meizhan, and by the end of the year all three of us were groupwatching things together—a regular pastime that continues to this day.

Around that same time, Kenji had founded a fansubbing group, SenritsuSubs, by which he became the leader of the effort to translate Osamu Dezaki’s legendary 1975 series The Adventures of Gamba. At the beginning of 2018, sensing an opportunity for The 11 Cats to be translated by him and his collaborators, I decided to reach out to him through Lilly, a mutual friend of ours, sending over my translated credits and information in the hopes that they might be included in a possible translation; while, due to a number of complications, the job could not be finished at the time, it was nevertheless the beginning of my friendship with Kenji, which eventually led to my involvement with Senritsu on their translations of Ganso Tensai Bakabon and Magical Princess Minky Momo (as well as the final release of Gamba).

Throughout 2018, I continued making preparations for a possible translation of the film. For one thing, I decided that I had zero interest in simply slapping subtitles onto what was then the sole existing online copy of the film in the original Japanese, which was taken from a TV recording and abysmal in almost every respect, and calling it a day; the film had, strangely, received a dubbed VHS release in Germany from Taurus Video in the late 1980s, and I realized that, by tinkering with elements like the saturation and brightness on the higher-quality YouTube uploads of this German release, I could obtain a vivid picture with better resolution and color than the Japanese version. That summer, I took the time to watch the Japanese and German versions of the film side-by-side to see what was missing or even edited out between them, with plans to eventually edit together a version of the film as complete and high-quality as possible.

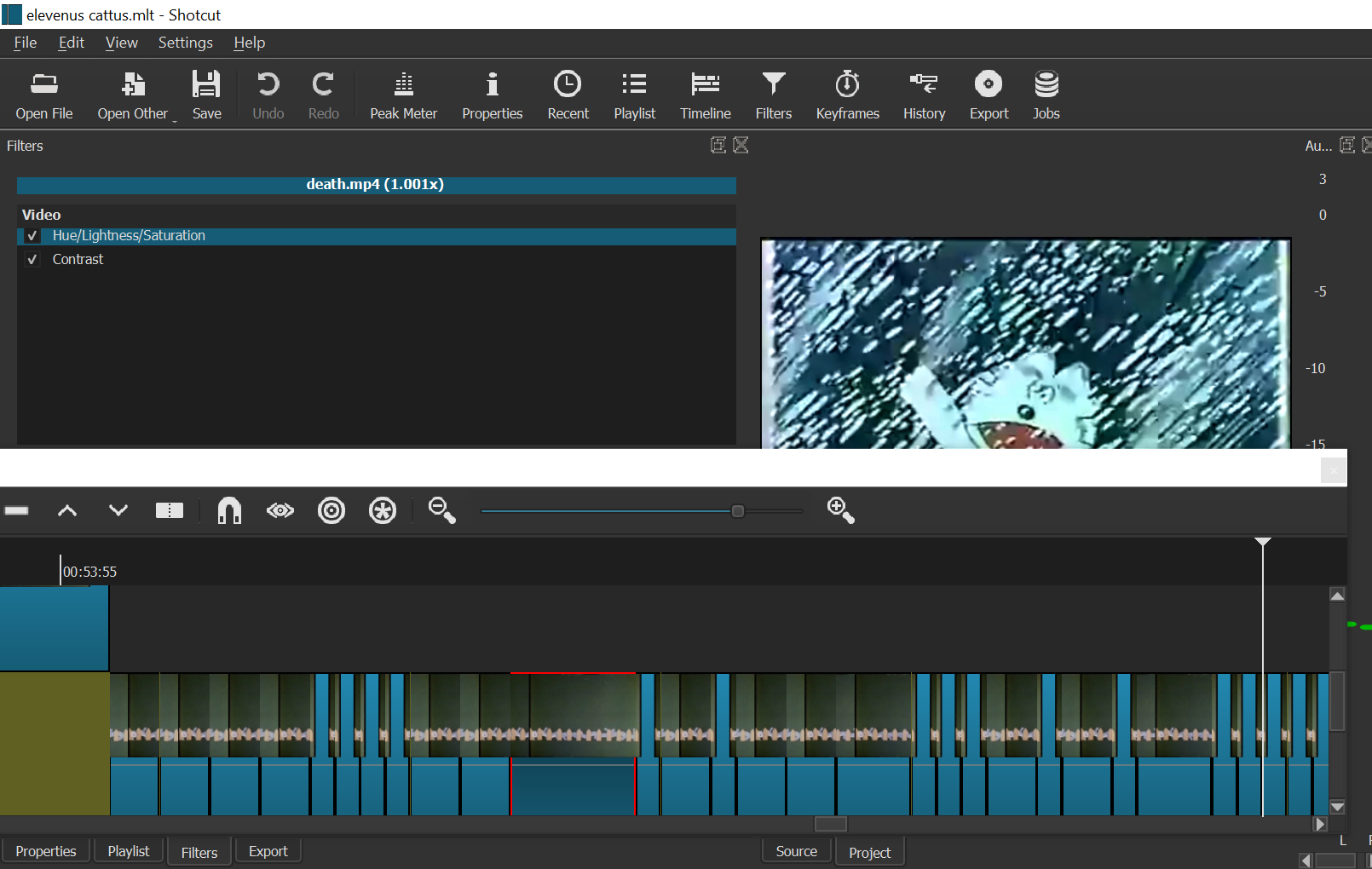

By November 2018, I had begun using the free video editor Shotcut to create my retrospective reel for the great animator Manabu Ōhashi, and on New Year’s Day 2019—at the same time as that reel was still in progress—I decided to begin working on a faux-restoration of The 11 Cats as well. The main video source would be this upload of the German VHS of the film; the one copy of the Japanese version would be relied upon mainly for the audio, as well as scenes that were edited from the German version.

One interesting advantage of using the German copy as the main video source was that, since it ran at 25 frames per second (PAL video format), it could easily be slowed down to its proper 24 fps (or actual film speed). This also meant, however, that the Japanese audio and video, which ran at approximately 23.976 fps (owing to the NTSC video format’s use of 29.976 fps, and the 3:2 pulldown necessary to convert a 24 fps film to that rate without a significant change in speed), both had to be sped up slightly (about x1.001) in order to properly keep time with the German copy.

The working process from here was thus: on the Shotcut timeline, there were two main video tracks, with the top track containing the German footage—color-corrected according to the needs of a given sequence, I very quickly found out I could not apply the same hue, saturation, brightness, and color-grading settings to the whole film (bringing the saturation up too much would often result in certain visual details disappearing)—and the one below it containing the Japanese footage. The Japanese audio was on its own track: the Japanese copy was annoyingly out-of-sync to begin with, so it was necessary to put the audio in a slightly different position from where it had originally corresponded with the Japanese video track in order to resynchronize the two. The German and Japanese versions were synchronized such that the opening scene with the papers tumbling appeared in both tracks over the exact same time frame, and I began painstakingly going through the film in both versions from there: by toggling the German video track on and off at specific moments, I could easily compare it with what the Japanese video track was showing at those same moments, and ensure they were still in synchrony with each other (and with the audio). If the two video tracks matched, I could delete all the Japanese footage up to that point, essentially marking the German footage up to then as being in proper synchrony with the audio; if, however, they were off by even one frame, I would go back to the preceding scenes in an attempt to find out where the discrepancy occurred, and make necessary changes from there (e.g. copy-pasting specific frames to get a relatively static shot or animation cycle that was shortened in the German version back to how it was in the Japanese version).

The first attempt to create a faux-restored copy of The 11 Cats had petered out by the middle of March 2019, owing to busyness with other things at the time (not least of which was preparing to graduate from UT Austin), and the project was put on hold for several months. I can’t remember exactly when I realized that the following year would be a better time to release a translation of the film anyhow, owing to its 40th anniversary; in any case, when, on 5 January 2020, I decided to return to the Shotcut file I had saved for the faux-restoration project, I discovered that the work I had done on it thus far had several problems—the best thing I could do was to start it over from scratch. By the end of that day, I had managed to redo all the work I had previously done—the first 19 minutes of the film were now the color-corrected, 24 fps German footage, properly matched with the Japanese audio—and from there I trudged forth, working well into the late night on some days, until, by 18 January, I was able to render the first pass of the faux-restoration. Additional revisions would follow as I noticed more problems that needed fixing, all the way up to just two days before this release.

To begin with, the main video source suffered from conspicuous tape damage during two scenes, namely the pan towards the 11 Cats’ base at night (right after they get chewed out by the police chief towards the beginning) and one of the cats futilely trying to exhort another of them not to cry after the supposed death of Commander Tabby. Luckily, there was another, lower-quality upload of the German version that had these scenes in relatively good shape; even then, however, I had to engage in strenuous color correction in order to properly splice these scenes in with the footage from the main source. (The aforementioned pan was particularly difficult in this regard, as part of it suffered from rapidly-fluctuating brightness levels, resulting in me having to correct the colors almost frame-by-frame in order to keep them relatively consistent.)

Additionally, there were several moments in which the Japanese audio suddenly dropped out and went silent. Many of these were a direct result of the Japanese copy being a TV recording, with the video itself freezing up as it led in or out of a commercial break, and in these instances I was able to splice in the equivalent audio from the German version; others, however, were much more inexplicable, like a small part of the film’s theme song disappearing as the 11 Cats march past the town hall (around 15:46) or—in the most egregious instance—the entire copy freezing up for several seconds right as the cats repeatedly shout “Ei ei oh!” in celebration of their victory over the big fish (around 1:16:43). In the former case, luckily, the music at that point consisted only of repeating bars, so I was able to copy-paste the exact same music from just a few seconds later to where it was missing with no sign that any editing was done; in the latter case, unfortunately, taking out the silent portion of the audio track still left a noticeable gap in the audio of the cats cheering, and for obvious reasons I could not use the German audio for that scene, so I ultimately had to try patching it up using slightly earlier audio of the cats’ “ei ei oh” shouting—even then, there remains a noticeable audio blip from the music not quite matching up. (In a similar vein, the Japanese copy was missing a bit of footage around the 18:14 mark as the cats march into the first town on their journey, including the tail end of the preceding song, and the German audio could not be used here because the songs’ timing and instrumentation were different in the German dub; I did manage to copy-paste the audio of the cats’ footsteps so that it undergirded the missing footage as it appeared in the German version, but the song itself jarringly cuts off for this reason.)

In addition to the original opening and closing credits, two pivotal scenes that were significantly shortened or censored in the German version had to be sourced at least in part from the Japanese video source: the scene of the cats conversing after their emotional reunion in the aftermath of their unsuccessful attempts to strike it out on their own, and the shot of Commander Tabby seemingly falling to his death. As I eventually realized, it was impossible for Shotcut to bring the 29.976 fps footage down to 24 fps without the sequences in question looking jittery after being rendered into a video file; as such, I re-encoded the conversation scene and the opening and closing credits to run at the proper 23.976 fps (effectively reversing the NTSC-required 3:2 pulldown), and then spliced those versions into the timeline (while speeding them up by x1.001 to make them run at 24 fps, of course), allowing them to run smoothly again. For the conversation scene—as well as a few other bits and pieces (even individual frames) that were missing from the German version—I also had to do color correction and even realign the video (yes, rotating and scaling it and slightly repositioning it on-screen) so that the film could transition as seamlessly as possible between the Japanese and German sources.

Unfortunately, this re-encoding could not be done for Tabby falling to his “death”: the interlacing of the original Japanese source ruined that scene and its animation timing to such an irreparable extent that I actually had to reconstruct it frame-by-frame, using intuitive guesswork to pin down the timing of his falling; it helped that the snow blowing in the wind, for one thing, was animated on twos, as a look at the scenes where it showed up afterwards in the German version made clear. (The part of the opening title scene in which the cats jump out from behind the fence pickets, with the film’s title appearing above them, was similarly reconstructed on the basis that, again, as seen in the German version which replaced the Japanese title, it was on twos.) But this created an additional problem: Shotcut’s struggle to scan through numerous individual frames during that scene resulted in the audio there crackling after the video file was rendered. In the end, I could only “solve” this problem in the final video file by rendering the video and the audio separately, then merging them back together using Avidemux.

Each of the smallest rectangles on the timeline as pictured here represents a single frame…

All of this does not even mention what an excruciatingly laggy, clunky, and crash-prone program Shotcut itself was in dealing with this kind of meticulous editing, to say nothing of the enormous amounts of power it used and the scorching heat it created on the surface of my laptop even when it was not rendering; suffice to say, it took immense patience on my part to even try creating this faux-restoration, and when all is said and done I can only be thankful that my laptop is somehow still in relatively good working condition. I could go on and on about the various other difficulties I encountered in editing this version of the film into existence, and the obsessive tinkering required to pull various things off—for instance, the insane difficulty of color-correcting the first few seconds of the film (in which Commander Tabby seems to stretch his body out behind the fence pickets) so that the colors could match those of the aforementioned Japanese-sourced scene with the cats jumping out to form the title card, frankly even now I’m still dissatisfied with how it turned out—but for now I would say these were the biggest problems I had to deal with.

As for actually translating the film, it was only on 11 March 2020 that Meizhan was able to find time to begin working in that regard (largely because the COVID-19 crisis was ramping up at that point, cancelling many of his other commitments—not gonna lie, I wish it had been under less unfortunate circumstances that this was done); by the following day, he had finished a rough draft with most of the dialogue translated (but not the songs), and using Aegisub I began editing and timing the first several lines up to the 11:20 mark. (I had already formatted the opening credits for the film as far back as 25 January, or Lunar New Year.) On the 15th, I gave the rest of the editing/timing work for the dialogue to Kenji as a thank-you for his previous attempts to get the translation project going (and for teaching me the ropes of subtitling), and he finished it up on the 28th that month; his distinctive imprint as a fansubber is clearly evident in the final script, hence his credit alongside Meizhan for the English subtitles.

When it came to the songs, I was luckily able to transcribe and set the timestamps down for the main theme songs that play throughout the first 21 minutes of the film, upon the cats’ reunion at the 29-minute mark, and of course at the very end of the film, making Meizhan’s job a little bit easier (translation requires knowing what is actually being said in the original language to begin with, hah); there had long survived images of a record that featured those songs, with their lyrics being printed on its back cover. I was unable to properly transcribe the other songs in the film, but nevertheless by 6 April I had gotten all the timestamps for the song lyrics down for Meizhan to fill in later; exactly a month later, he managed to finish translating most of the songs, and an additional two months and a day after that (7 July) he finished off most of the remaining song lyrics and all of the problematic bits of dialogue left. (The two remaining lyrics were filled in the following day by Nearra, who had been Kenji’s translator on Minky Momo.)

The back of a record containing the two main theme songs in The 11 Cats, featuring the lyrics to the songs in question.

A day after this original release, commenter Iri kindly gave me a corrected translation for the melancholic song that plays after the 11 Cats’ first encounter with the big fish. I have since uploaded a second version of the Google Drive file with these corrected lyrics (thankfully the link remains the same), and added them to the YouTube upload as an additional caption track (please be sure to enable it if you’re watching the latter version!); the advantage of these platforms is that it is easy to correct these mistakes without breaking the original links, in case they get shared around separately by others.

By no means is this a perfect release of The 11 Cats—the very fact that it had to be composited from YouTube uploads of various VHS recordings of the film prevents that—but it may well be the best way to view the film for the foreseeable future, at least so long as the rights holders continue to keep it buried without any hope for a proper restoration and release. With this project, all of us involved worked hard to give the film (and for that matter Fujimoto’s three best Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi segments) the proper exposure it deserves, and I would not have it any other way; time will tell, perhaps, whether our efforts were ultimately as fruitful as the 11 Cats’ quest for the big fish.

BONUS: On its original release, the very end of the film actually had an additional scene in which the 11 Cats scramble in and bow down to the audience as “The End” pops up above them. Unfortunately, this presently survives only in a bad-quality recording of the Korean dub, and accordingly could not be used in my reconstruction of the film…

Notes:

- ^ Dezaki’s sole episode at the time, #47 (雷さまと桑の木), aired 10 April 1976, remains one of the series’s all-time masterpieces, if not one of the purest expressions of his unique way of seeing the world. Its animator, Takekatsu Kikuta, had been one of the top animators on the original Ashita no Joe at Mushi Pro in 1970, and like some of those animators followed Dezaki over to Madhouse in 1972 to work on the earliest episodes of The Gutsy Frog, followed by Jungle Kurobee and the 1973 Aim for the Ace! series (for which Kikuta even storyboarded episodes 17 and 22); at this point, however, Kikuta had gone freelance, with Madhouse proper working on Ganso Tensai Bakabon and episodes 11 and 18 of Dino Mech Gaiking.

- ^ Unlike the other key ex-Pyuta staffers, Takeuchi was by this time based at Ryōsuke Takahashi’s freelance collective Akabanten; independent animator Tadahiko Horiguchi and Tetsuo Yasumi also worked on the series from here. Takeuchi’s sole outing for MNMB at the height of his powers was animation for Takahashi’s #41 (梨とり兄弟), aired 13 March 1976, and it is not hard to see why Maeda likely did not want him going anywhere near the series again.

- ^ Kawajiri had just left Madhouse after the end of that studio’s involvement with DAX’s Manga Sekai Mukashibanashi, on which he gained his first taste of being a designer-filmmaker in his own right and began developing the visual style of his later films; he refused to work any longer under Osamu Dezaki (with whom he was on the outs at that point) on shows like Nobody’s Boy Remi and Treasure Island, which succeeded MSMB on Madhouse’s production schedule, and would only return to the studio towards the end of 1978 (or the beginning of 1979) as Dezaki became increasingly less dominant there (he and his frequent collaborator Akio Sugino would themselves end up leaving shortly afterwards to found their own studio, Annapuru, so they could focus full-time on Ashita no Joe 2). During this brief spell as an independent animator, Kawajiri also animated the first episode of Hayao Miyazaki’s cult classic series Future Boy Conan alongside Yoshifumi Kondō, and even created a charming music video for NHK’s long-running interstitial program Minna no Uta.

- ^ With a paradoxical and interesting modernist edge, it must be said—particularly evident in the first 25 or so half-hours which featured original scores by modern classical composers, reminding this writer of how Czech animated films from this same era often featured scores from such great composers as Zdeněk Liška, Luboš Fišer, and Jan Klusák, and underlined by how most of the monthly endings for the series (with the exception of those for January and July, the latter of which was rather horribly animated by Nobuko Abe) were created by Takao Kodama in his own charmingly offbeat geometric style. (Sadly, of Kodama’s endings, only the ones for June, August, and September are available to watch.) A number of the episodes were even written by the famed Japanese playwright Minoru Betsuyaku, who years later would also write the screenplay for Group TAC’s crowning achievement as a studio, Gisaburō Sugii’s 1985 adaptation of Night on the Galactic Railroad.

- ^ Many of these musicians would reassemble under Hitoshi Komuro shortly afterwards on a strange Sunrise-produced 1982 TV film, Shiroi Kiba: White Fang Monogatari, based (of course) on Jack London’s novel White Fang; it was directed by Sōji Yoshikawa, who is best known as the screenwriter-director of Lupin III: The Mystery of Mamo, and interestingly it also featured Group TAC president Atsumi Tashiro as audio director. To give a few additional tidbits on the musicians themselves: Eiryu Kou has had a long and varied career as an electric guitarist, with one of his most notable stints being as co-founder and guitarist of the cult heavy blues rock band Ranmadou (乱魔堂); Takahiko Ishikawa collaborated with the great Haruomi Hosono and his colleague Masataka Matsutoya on the 1979 album The Aegean Sea (Hosono, of course, went on to compose the music for Night on the Galactic Railroad), and later released a number of solo albums like this one; Masahiro Takekawa was the violinist in Keiichi Suzuki’s seminal bands Hachimitsu Pie and Moonriders; and Kōichi Matsuda served as a studio harmonicist on various albums for over 30 years, more recently even releasing a few solo albums (here is a track from one of those albums).

Thanks for the subtitles!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I noticed a few mistakes in one of the songs (at 1:04:30 in the 11 Cats Youtube video), so I took a swing at it myself. I think I’ve managed to hear all the lyrics properly, though my translation is a bit of a rough draft in need of polishing.

Translation with romaji here:

https://pastebin.com/28kELXrh

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! As of this writing, I’ve uploaded a new version with the corrected lyrics (polished by me, of course) to the Drive, and I’ve also added them to the YouTube upload as a new caption track – and your name has been added to the sub credits at the very end, of course. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this!

A couple of months back I randomly stumbled upon this restoration on some torrent site. And today, I stumbled upon this blog post.

Thank you so much. You made my day a while back, and you’ve made my day again 😊😊

I had this on VHS as a kid. Original audio and Danish subtitles. I don’t know where it came from, and my parents don’t know either. I think it may have been bought second hand.

I had never seen the first part of the film. My copy starts with them being reunited in the desert. The first part of the tape was damaged completely, and was eaten by the VHS. My father had to cut out the damaged parts to make it work again.

By the way, I believe the VHS still works. I am going back home on Friday, and I can check. Maybe I can rip it for you, or send it your way.

The Danish subtitles are hardcoded, of course, but it may help in restoring some of the scenes further, or for recovering the “The End” bonus scene.

Let me know if you’re interested.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Aksel,

Very glad to be of service in bringing your childhood memories back – and wow, I had no idea the film was also released in Denmark! I vaguely remember reading that there was another dub/release of the film in a different Scandinavian language (Norwegian, I think? I can’t find the database entry right now); it’s good to know that the film got quite a bit more exposure outside Japan than I previously imagined.

Yes, I would love to see your version, if you are able to rip it. Even if the first half is missing, it’d be nice to have it around for archival purposes (and I just might do a v2 of my semi-restoration after all, aha). While I’m at it, I discovered today that the film was even released in Finland, albeit it was a Swedish audio narration dub with Finnish subtitles (though unlike the German version it does seem to keep the Japanese titles): https://aninjaaritukset.blogspot.com/2018/02/11-nalkaista-kissaa-ja-kaverihenki.html

LikeLike