UPDATE (3 November 2023): See the comments section for some additional memories and insights from cameraman Ivan Vít, who worked as a technical assistant on most of the films discussed in this article (and on the second Bears series and The Appletree Maiden, for that matter).

Today, 7 October 2023, marks exactly 100 years since Czech animation legend Břetislav Pojar was born. Such a momentous occasion deserves to be commemorated in the grandest way possible: what better way, therefore, than to present a translated career-spanning interview with the man himself, and to offer several more observations and production details on some of his most beloved films?

Actually, before we move on, I must make a formal announcement: henceforth, On the Ones is truly no more, and I have decided that this will be the last article I write on animation history. In truth, keeping the blog semi-active has always felt more like an obligation than a real passion project; this sense of duty could be kept burning for as long as I still had the passion to keep watching, researching, and writing about international animation. Over the past year or so, however, my interests have shifted dramatically, and I feel that I’d much prefer to focus my time and effort on other hobbies and duties I’ve mostly neglected, especially now that I find them much more pleasant and nourishing. I have even wondered in the past several months if so much of the misery that dominated the past several years of my life was a direct result of trying to enter the animation blogging sphere, and if it really was all just a giant waste of time and energy and emotion that should have been expended on far more nourishing aims.

There is a certain poignancy in how, just as my two articles on Pojar in late 2016 and early 2017 were how this blog got going as mostly a solo-project, so too will these last few mega-articles on Pojar ultimately be how it ends. In a way, though, my devotion to Pojar and his films is arguably the ultimate reason why this blog is coming to an end. When I learned in early 2020 that transcripts for his two most beloved series, the Bears and The Garden, were bizarrely hidden inside the HTML code of Czech Television’s pages for Mistři českého animovaného filmu and the Bears series’ reruns (unfortunately, the website has since undergone a revamp, and all those subtitles are no longer there), I knew that I had to not only translate these films, but also discuss them in more detail than I had in those old write-ups. The latter desire was only reinforced by how, towards the end of March, I made the acquaintance of Marin Pažanin of Ajetology; through the e-mail interviews he began conducting with animator Jan Klos and others, the two of us learned far more about the history and making of all these classics of Czech animation than either of us ever would have dreamed.

The actual experience of translating these series and creating subtitles for them very meticulously—a process that, by its very nature, made me watch the films over and over again and even study them frame-by-frame—did two things to me. The first thing was that it awakened a new desire to focus more on translating obscure works instead of just trying to write about them, and this is one particular new interest of mine that I hope to keep going for at least a little bit longer. The second, and more consequential, was that it made me really see just how intricately crafted and meticulously animated these films were; combined with the influence of Marin’s own keen eye as far as spotting interesting details and production mistakes, I decided to try making my new articles on the Bears the definitive write-ups on the series, analyzing every bit of character acting and various other elements and unnoticed details as much as I possibly could.

In writing these articles, I would always literally re-enact what the Bears did (at least, to the best of my non-transformative abilities) in front of my computer, to get a sense of what they were thinking and conveying with even their slightest gestures. It really is a testament to Pojar’s acting ability—and to his animators’ own talents—that they really tried to get this kind of character acting across, with many very specific movements and timings that I certainly wouldn’t think of trying to animate on my own if I were an animator in their conditions. The downside of trying to figure every single little detail of their acting out, though, and for that matter observing every single little error or whatnot that I could find, was that the articles kept ballooning more and more to increasingly unsustainable levels, with seemingly every further article outdoing the last in terms of length and content. Their influence would wind up spilling over into my New Moomin article earlier this year: I had specifically intended it to be a series of much shorter write-ups when I began writing it last November, but it soon became obvious that my overanalyzing habits had become second-nature, and it very quickly evolved into a practical encyclopedia of lengthy episode analyses in themselves.

All the while, my active interest in animation began to subside, and it was hard to really work up the motivation to start writing again after my New Moomin article. When I finally sat down to begin writing about The Animal Lover sometime in July, I only wrote about the first four or so minutes of the film before I realized—I had already written tons of paragraphs attempting to detail and decipher even the most minor gestures of the old gentleman and the fish and the gnome without really getting anywhere, and on top of that, I no longer had any real sense of fulfillment from writing, let alone any motivation beyond Pojar’s centennial. So it was that, after consulting with friends, I decided to scale things back significantly: my final article would be a two-parter, the first being an entire translated interview with Pojar and the second being a series of mostly shorter write-ups on The Garden, Dášeňka, and Nightangel, bridged by the overall history of Pojar and his studio Čiklovka. The write-ups on The Animal Lover, Of That Great Fog, and Nightangel, in particular, are essentially revised versions of my previous write-ups from February 2017. (The first two are also significantly reorganized and expanded with more details—unfortunately, I couldn’t really do the same for my Nightangel review due to time constraints, it really was only last night that I finally got to that section of the article…)

Once again, very special thanks must go to Marin Pažanin and the folks at Animation Obsessive, who in a real sense deserve to be considered the co-authors of this article. Aside from Marin’s valuable interviews and AniObsessive’s valuable resources (they provided, among other things, the interview with Pojar translated below, which I had already quoted in my previous article on the second Bears series), many of the observations in the write-ups below were taken from very insightful conversations I’ve had with them over the years.

With Head In the Clouds and Feet on the Ground

Taken from the Czech National Film Archive’s anthology “Animace a doba” (Animation and Time), which was published in 2001.

Stanislav Ulver: Can you describe the genesis of the creation of your first two films, shot in the early fifties, which differ quite substantially from each other, and not only because the first of them is a classic fairy tale and the second (about a motorcyclist who doesn’t resist the invitation of the wedding guests and then cannot drive while drunk) a story from the “hot present-day”?

Břetislav Pojar: In the case of The Gingerbread Cottage (Perníková chaloupka), I was entering Trnka’s own field, which was to a certain degree conditioned by the fact that I was starting out and had to take the theme that they offered me. It was an older script, it had already been lying in the studio for some time, and I could only rework it thoroughly. It was just at the time when they definitively rejected Trnka’s film about Matěj Kopecký and suggested that he make Old Czech Legends. The studio was idle in this interim and it was necessary to fill the break with something—and so I got an offer to do just that. Maybe also because I always ran away from the studio—to a live-action film, to a documentary, anywhere. I simply already wanted to direct back then. But since it was a fairy-tale story which was Trnka’s own, and the puppets which he created for The Gingerbread Cottage were also quite similar to his illustrations from children’s books, it began to be said that it was a Trnka-esque, imitative film, and that naturally ate at me. In fact, there is already a whole series of elements on display here which I used later, for instance even in the Bears.

That’s why when I started preparing my second film, A Drop Too Much, I was quite careful that a similar Trnka imprint did not turn up in it. I started looking for inspiration elsewhere, for instance in Kamil Lhoták and artists who came from the so-called civilizational circle. Another source of inspiration for me was the Italian neorealist wave. So the second film was created in a substantially different way from The Gingerbread Cottage, and even my own experience left its mark on how it came across as believable—the fact that I also had a motorcycle and rode it a lot.

Ulver: It was probably one of the first films ever where a puppet scene gained such great dynamics.

Pojar: Yes, it was. The theme itself demanded it and it was difficult to figure out how to do it, because building a long enough scene, down which a motorcyclist would speed, was not possible in the studio. In order to be able to express the needed movement at all, I had to use a slightly different, typically animated solution—moving the background, and not the puppets. Unlike Trnka, who was an illustrator and scenographer—and although he had a command of film language, he liked to proceed from static, artistically-conceived images, which he could sometimes use very effectively even without movement—I was fascinated mainly by film possibilities and movement.

Ulver: If we were to follow some kind of main developmental line in your work, would The Little Umbrella come next?

Pojar: As far as animated film is concerned, well, yes. But in the meantime, I filmed another live-action story for children, The Adventure in the Golden Bay. At that time I even thought about staying with live-action film, but back then, the conditions for approving scripts there were so binding that I preferred the freer animation.

Ulver: Was the script of The Little Umbrella your own?

Pojar: The Little Umbrella was actually created, after all, like most of my first animated films, for a commission. Vratislav Blažek came up with the script, a kind of puppet show. But he was a theatre author, who worked with words. And in the studio, we agreed at the time that shooting something similar with puppets made no sense. So I threw it away and wrote a new script myself. I based it on real, even if sometimes a little exotic, children’s toys, there even appear Chinese dragons or maybe a bubble boy. The basic figure is Andersen’s sleep-luller Ole Lukøje from Jiří Trnka’s workshop, other figures and decorations were made by Zdenek Seydl, except for the cube wall, which was designed by František Braun.

Ulver: Then you collaborated with Seydl many more times?

Pojar: Yes, he was an artist who was completely different from Trnka—and I chose him quite deliberately. And right after The Little Umbrella, I did The Lion and the Song with him.

Ulver: Was that the most famous film of this creative period of yours?

Pojar: Perhaps surprisingly, A Drop Too Much was even more famous, even though it was about an anti-alcohol theme. This film went around maybe the whole world, besides the main award in Cannes, it received many others and was instrumental in my international reputation!

But to return to The Lion and the Song. As designer I chose Zdenek Seydl, because he had great experience from the National Theatre, for which he successfully designed ballet sets with gorgeous costumes. A single hitch happened then: Seydl originally wanted to use painted decorations on glass, perhaps according to Trnka’s model, but he thereby made it so ornamental in his way that the figures were not visible against it. In the end, we agreed on a plastic three-dimensional set. It had a more beautiful finale when the oasis was built, everything lit up and ready for filming, I called him to come take a look. He was silent for a while, and then he said: “That’s some stupid 19th-century romanticism.” And all I heard after that was the slamming of the door. Then when he saw the finished film, he apologized to me and retracted everything.

Ulver: The film had great success in 1960 in Annecy, where I think the first year of the future most famous international animated film festival took place.

Pojar: It won the first Grand Prix there…

Ulver: Were you particularly interested in the poetic position?

Pojar: In this case, yes. Finally, the inspiration here was Henri Rousseau’s painting The Sleeping Gypsy, and also a bit of Chaplin. Then I was lured by quite different themes…

Puppet films were actually just starting at that time. They did not have such a long tradition behind them as cartoon films did. Before the war, only a few of them were created, and after that they were made only for a short time here. Each of the creators of that time, Ms. Týrlová, Zeman, and Trnka, were back then still always discovering the possibilities of this genre in their own ways and figuring out what could be done with those dummies. Even I, when I was starting out in the fifties, strove to bring something new with every film.

So A Drop Too Much differs quite significantly from The Little Umbrella, which we talked about a moment ago, and of course also from The Lion and the Song and the other films which followed – How to Furnish An Apartment? (Jak zaříditi byt?) with a popular scientific theme, The Midnight Story (Půlnoční příhoda), which was a modern Christmas fairy tale, and Bombomania, a cartoon satire on atomic armaments which was to commence a series of satirical puppet films.

Each of them was a step into unknown territory—unknown thematically and technically—because even the puppet technology was constantly changing. It worked back then. They could be varied and they didn’t have to be for children, because they were shown as a sort of “appetizer”, as Mr. [Jan] Werich said, before the main film in cinemas. It’s a shame that this option no longer exists today. Authors can present their works at most at festivals or in film clubs, and unfortunately there aren’t enough shows like those here.

Ulver: Did you have any problems with the line that you call satirical?

Pojar: Very soon they forbade it, as far back as in the bud. It was exactly Bombomania, which I made at the studio Bratři v triku at the same time as The Lion and the Song, which got me in trouble. Both of those films suddenly aroused great displeasure, so they devoted an entire half-page to me in Rudé právo [the official Czechoslovak Communist newspaper] called “A Pitfall in Czech Animated Film”—and the “pitfall” was me. As a result, even [Jiří] Brdečka had problems with his film Attention (Pozor). From that time on, I had to submit all the scripts to the central directorate and every project of mine was censored. It took quite a while. But the worst thing was that I had prepared a whole series of scripts of a similar type, and I had to throw them all away and make films for children.

Ulver: Is this the indirect start of your very successful poetic line for children and adults?

Pojar: You probably mean the Painting for Cats (Malování pro kočku) series…But in the end, I was able to carry out the planned satires after all, even if Billiards, A Few Words of Introduction, Romance, and Ideal no longer had any great political subtext, at least in my opinion.

Ulver: But the audience probably found it there…

Pojar: It depends a lot on what kind of situation the film will then come into. Bombomania was shown in Tours at a time when France was testing its first atomic bomb, and after all the commanding general was a tall, asthenic type like De Gaulle, so the French were rolling with laughter, although of course it wasn’t intended to be that way. For that matter, Trnka’s The Hand also deals more with the creator’s private problems, rather than society-wide burning themes. And in the case of A Few Words of Introduction, even I myself had doubts about whether it would be too boring a film, when I had already put in so much work and it had cost so much energy. But coincidentally (of course, on purpose) they played it before the opening speeches of ministry officials at many festivals, and it was always a catastrophe for them. The only one who more-or-less slipped out of it was the culture minister in Ottawa, who declared: “I had a very nice speech prepared, but after this film I’ll leave it for next time.”

Ulver: When we return to Painting for Cats and other films of this type, Rudolf Deyl is already appearing here as a commentator…

Pojar: Yes, here is actually where the foundations of the team with which I later made the Bears emerged. The author of the stories was Ivan Urban, the designer was Miroslav Štěpánek, the music was composed by Wiliam Bukový, and the real discovery was Rudolf Deyl, who read the narration. On the outside, he came across as a very “serious” actor, but here his “comedian” talents became fully evident.

Ulver: The Bears, or They Met Near Kolín if we proceed from the title of the first episode of this series, and The Garden, probably your best-known and most popular spoken films at home, probably clarify your rather skeptical remarks on the subject of the use of narration and dialogue in animated film only with difficulty.

Pojar: The spoken word, of course, enables you in animation to express what you couldn’t with a mute pantomime. Narration makes it easier to describe complicated situations and a puppet’s voice enlivens, it gives them credibility and helps express their character. In addition, working with language is beautiful and entertaining. Trnka, granted, never wanted his puppets to speak, but he simply had to cross that threshold.

But for Czech animation, as I later found out in the case of the Bears, and then in particular The Garden, this is not the way to go. At home, you put a lot of work into the narration or dialogues. You choose the perfect speaker, you see to it that the text is humorous and optimally written. But when someone dubs a film in foreign countries, they usually only choose a cheap actor of the fifth category, God only knows how they translate the dialogues, if the translator understands them at all in the case of such a special language as the Bears speak to each other, and in the end they will still adjust it all “artistically” if need be…

Ulver: In what sense?

Pojar: I saw a version of the Bears in Berlin, where the dubbing director had the little one speak in an even more squeaky voice than what Deyl had, and the big one with a baritone like I have. Then it looked like when a bad uncle tortures a poor little boy—and everything was screwed up.

In Mamaia, granted, one episode of the Bears won the Grand Prize and people liked it terribly [Pojar is referring to how Princesses Are Not To Be Sniffed At won the Golden Pelican at Mamaia’s first International Animation Festival in 1966], but such a film is unusable for foreign television, for instance. It’s impossible to subtitle, it would lose half of its charm, and I don’t believe that anyone would dub it well. It costs a lot of money and the distributor decides to do this at most for a feature project or a large series.

Ulver: The semi-relief puppet was used very prominently in the Bears…

Pojar: I had already started with it much earlier, in Billiards and A Few Words of Introduction, a different type of relief puppet was used in the case of Romance, and a completely different one in Ideal, so that I had quite a good deal of experience with absolutely different types of puppets. And since in the Bears it was about metamorphoses, the semi-plastic form appeared to be just the most advantageous.

Ulver: In what do the main differences lie?

Pojar: A classical puppet is like an actor who can play anything when it has the firm boards of the stage under its feet. But if it has to break away from them and jump gracefully, troubles will arrive.

Ulver: In your interview from 1957, you speak among other things about the need to fly with classical puppets, and then you made it happen.

Pojar: Yes, already in The Little Umbrella. When the script requires flying, you have to force that heavy and unpliable mass to do so. But it is always difficult. If you don’t need movement into the space, it is animated with a vertical camera on glass. For spatial movement, it hangs on nylons at three points, Archimedes already discovered that, but to make a fluid movement in this way is really an art. You can also use special effects, but even that is very complicated, especially if you do it directly on film. The easiest thing to do today is to use a computer.

Ulver: In the case of The Garden, which is probably the closest to the Bears in its poetics, you alternated diverse techniques several times. Why?

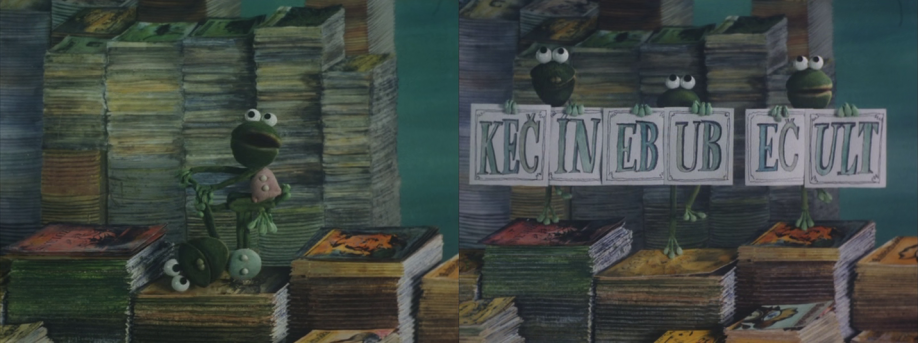

Pojar: Because I discovered the advantages of combining them. Just as with flying, it is difficult to animate four-legged and multi-legged animals in classical puppets. The metal skeleton works quite well when there are only two legs, but with a horse, for example, it is already a four-legged problem. I know what I’m talking about, horses were my frequent destiny in Trnka’s films. It can be managed in the end, but you have to invent various gadgets, auxiliary machines and so on, and that’s why in The Garden, where there were elephants, a tomcat, and a whale, it seemed much more advantageous to me to join classical technology with relief. But the use of semi-plastic puppets has one catch. The animator actually assembles them on glass from the individual parts, and he must be very good, to always maintain the artistic character of the figure in every gesture. I was very lucky. My main animator, Boris Masník, could do it perfectly, and the way he animated the Bears or the lads and the animals in The Garden was a genius animator’s performance in all respects.

Ulver: How do you give the puppets expression at the same time? Let’s take, say, the Tomcat from The Garden as an example.

Pojar: There was no problem with the Tomcat, I had already tested it there from the Bears. In The Garden, it was more about fairly realistically and classically conceived lads who not only looked a certain way, but also spoke, even in sync, because when it’s a dialogue of four figures, it cannot be otherwise. It has to be seen, which of them is speaking. It was quite a pain to figure out, but that’s already how it goes with puppets. Bringing matter to life is much more difficult than drawing on paper, you always have to solve new problems. But in a way, it makes the work varied, and ultimately even fun.

Ulver: What led you to return again to classical puppets in The Appletree Maiden?

Pojar: It wasn’t so completely classical. It was again, in a way, a commission on the theme of a Czech fairy tale. One of them, Smolíček, was done by Jiří Brdečka, another by Božena Možíšová. In my case it meant returning to puppets anchored on ground, but I must add that I actually already missed it a little, especially after working with space and greater use of lights and special effects, which is quite limited in relief film. In The Appletree Maiden, it was a lot about creating an atmosphere of mystery and enchantment. And another thing, which attracted me, was to do a tree giving birth to an enchanted maiden. It was, granted, an entrance into Trnka’s territory again, but I was no longer afraid of it.

Ulver: Towards the end of the 1970s, a socio-critical tendency again appears in your films like The Big If or Booom…

Pojar: These were themes commissioned by the United Nations, for which I made the films. But my return to social satire already took place before that. Just when the Prague Spring ended, I finished the film What the Earthworm Didn’t Suspect (Darwin Antidarwin aneb Co žížala netušila). That was the first thing I had to show the new management.

Ulver: Unfortunately, I haven’t seen this film. What bothered [Krátký Film’s new head Kamil] Pixa the most about it?

Pojar: It was again a certain political subtext. The earthworm dreams about a Darwinian evolution into an ever more perfect creature, but when it finally becomes a human and has the impression that it’s reached the height of freedom and liberty, it experiences such a paraphrase of a shortened history of Europe that it prefers to crawl back underground. Back then, I had several similar stories, for example E, which was later shot in Canada, which did not stand a chance here at the time. I returned to the Bears again.

Ulver: When did you first actually depart to Canada?

Pojar: In 1967. They let me go at the time for three months at most, so the first film I made in Montreal involved several such visits. At the time of that relative freedom, I also shot Balablok in Canada, which again had political consequences for them—the English rejected the story, as it could offend the French, but they took it immediately. You simply bump into something everywhere. But in the normalization period, there naturally came problems with traveling…

Ulver: When you shot Nightangel here in 1986, did you collaborate with Jacques Drouin from the beginning?

Pojar: The conditions had already loosened up and and I got out through the UN, for which I had made some films. As for Drouin, the Canadians themselves came up with a proposal to collaborate with one of their younger directors. I decided upon Drouin, who at the time had as his second film Mindscape, realized on pinscreen, but first I had to come up with a theme where both techniques would be joined together. In the end, we agreed together on exactly Nightangel. I originally thought that the puppets would be colored and the blindness, done on pinscreen, in black-and-white. But Drouin worked terribly slowly and his “part” was relatively long, so I suggested that the pins had to be colored, which managed to be figured out. I realized the extensive black-and-white part of the film with puppets in Prague. Drouin then did the colored dreams—there were far fewer of them, but they were important and turned out very beautifully. Even the combined scenes were successful.

Ulver: Did you also try working on that screen yourself?

Pojar: When [Alexandre] Alexeieff, who invented this technique, brought it into the [National Film Board of Canada], I tried it, but I lasted two days at most. Of course, I was not alone. Norman McLaren also experimented with it, but even he lacked patience. [On that note, here‘s a documentary that McLaren filmed in 1973, in which Alexeieff and his wife Claire Parker give a demonstration of their pinscreen to various NFBC animators and allow them to try it out. Among the artists featured are Ryan Larkin and Caroline Leaf.]

Ulver: I think there were more of those pinscreens…

Pojar: This was his original screen, around A2 format. Then he got a bigger one, and since he gained asylum in Canada during the war, like that he donated the smaller one to them with great splendor. Incidentally, two people had to work on that big screen at the same time. Alexeieff was assisted by Claire Parker, who returned pins to him from behind.

Ulver: Can we stop at your combined feature film Butterfly Time [known in English as The Flying Sneaker], completed in 1990?

Pojar: I’d already been thinking of a live-action film combined with animation for a long time. It was a bit of bad luck that this project started to arise right in 1968. Everything was already prepared and approved, even the script, but the troops of the Warsaw Pact interfered in it… Moreover, it was in the group at Procházka, where they were quickly, hastily finishing other films. [I am not too certain what Pojar is referring to here; if I had to guess, he seems to be saying that the film had been assigned to the husband-and-wife team of Pavel Procházka and Stanislava Procházková, who were Čiklovka’s two other animators besides Boris Masník in the 1960s. As mentioned previously, both would emigrate soon after normalization began, which would probably account for their haste at the time.] It was therefore realized as late as some twenty years later, and even if in its time such a combination was quite original, it naturally no longer is today…

And one more thing damaged this film. Originally, it was supposed to be costumed, with reality shifted thirty to fifty years into the past, but there was no money for such a grand intention. Maybe in a few years it won’t occur to anyone anymore. In France, Butterfly Time won many awards, including the audience prize, in England it again had good reviews, in China it was very successful, and in Germany it is distributed to this day, only here is it like it wouldn’t be…

No one ever knows how a film will work with the audience, if it “hits” its time exactly, if it comes too late, or too early. It’s a risk, especially when you’re trying something new. You simply have to be lucky. On the other hand, I think that testing was probably essential in my times. It helped create a foundation on which one can build, to balance the handicap of puppets compared to cartoon films, and to develop this field not only here, but also in the world. Even if today, in the age of digital technology, much of what my generation contended with is slowly becoming a mere history of the Stone Age of puppet film.

As usual, watch The Garden and Dášeňka on YouTube with English subtitles here!

Or, download copies for personal viewing with English soft-subtitles here!

When we left off, Čiklovka had just officially become a branch of the Jiří Trnka Studio, after a few years of administrative limbo. It was a move that made sense in terms of production efficiency. Čiklovka could no longer be devoted exclusively to films by Břetislav Pojar, Josef Kluge, or their close associates: henceforth, outside directors and staffers (predominantly from Konvikt, the actual Trnka studio on Bartolomějská Street) would occasionally be assigned to the studio to work on their own films, or even help out with the main staff’s films, as the need arose. Or, as animator Jan Klos rather cynically put it,

Krátký Film Prague often “exploited” the free capacity of Čiklovka by delegating various directors and their projects (I worked there for 9 and a half years mostly on Pojar’s projects, but I could also work with Václav Bedřich or J. Barta, for example…).

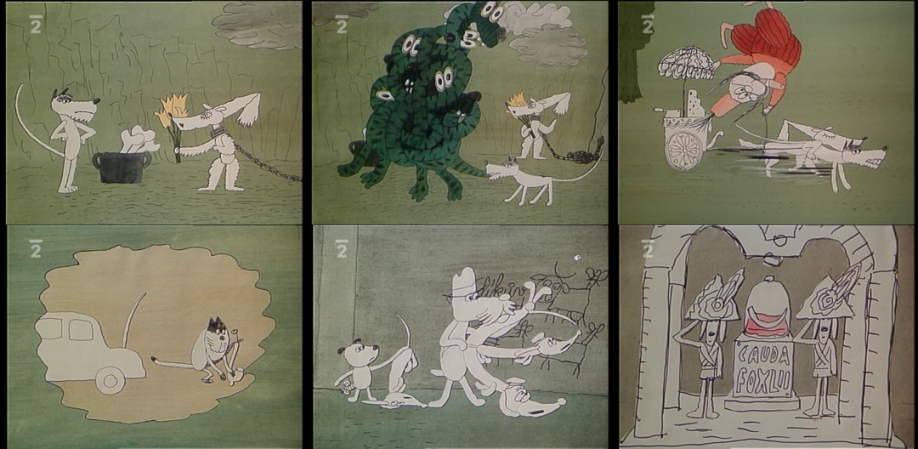

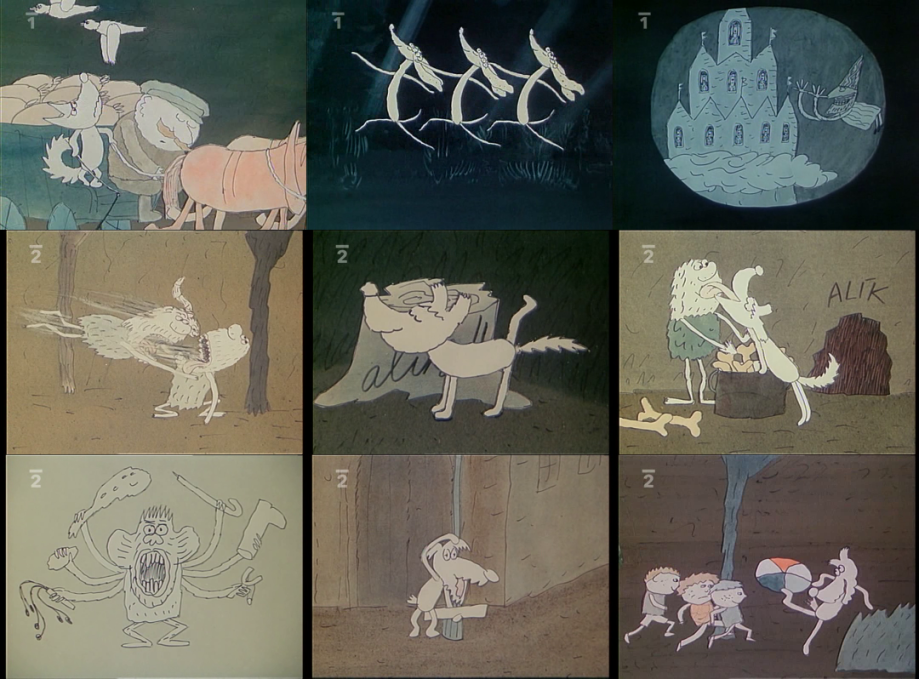

The first visitors from Konvikt arrived almost as soon as Čiklovka became part of the Trnka Studio. The second of Josef Kluge and František Skála’s hunting cartoons, Prach a broky, was animated by none other than the great Trnka veteran Stanislav Látal with soon-to-be-animator Zdeněk Vinš credited as one of the assistants (Břetislav Dvořák, otherwise Kluge’s main animator at the time, also served as an assistant here), and Látal’s energetic animation is largely responsible for why this entry is much more watchable than the first effort Parohy, its fast pace and intricate movement and acting (just look, for instance, at the whole sequence of the dog getting tired!) ensuring that the otherwise-routine gags involving a battle with a crafty hare are actually funny. Unfortunately, it does suffer from its overlong, underwhelming final gag of the hare sounding its horn in triumph; still, at just over 5 minutes, one cannot complain too much. (I would personally say it is the third-best in this series of Kluge-Skála hunting cartoons. As for my curt thoughts on Parohy, since I hadn’t actually seen it yet when I wrote my previous Pojar/Čiklovka article: some nice bits of design and animation, but I thought the gags with the cow and the two deer were just stupid, there are some sequences where the animation is noticeably lackluster and not nearly as fluid and fast-paced as it should be (hardly a surprise with B. Dvořák animating here alongside Boris Masník), and the attempted racy ending punchline was so insulting that I felt a bit of an urge to throw my laptop out the window, aha…)

Aside from the more frequent presence of outside filmmakers, however, Čiklovka largely retained its previous organization centered around Pojar and Kluge, and life at the studio remained as fairly isolated and provincial, if not familial, as ever. Given that the actual production work—whether it was crafting mechanical skeletons for the puppets to ensure their flexibility, building the sets, preparing and decorating the actual puppets, or animating them—was slow and quiet, the occasional breaks helped to foster a sense of community at the former sculpture studio located at Čiklova 1706/13a. These included joint lunches, sitting around in the garden, assorted addresses to the staff, and joint screenings of filmed material.

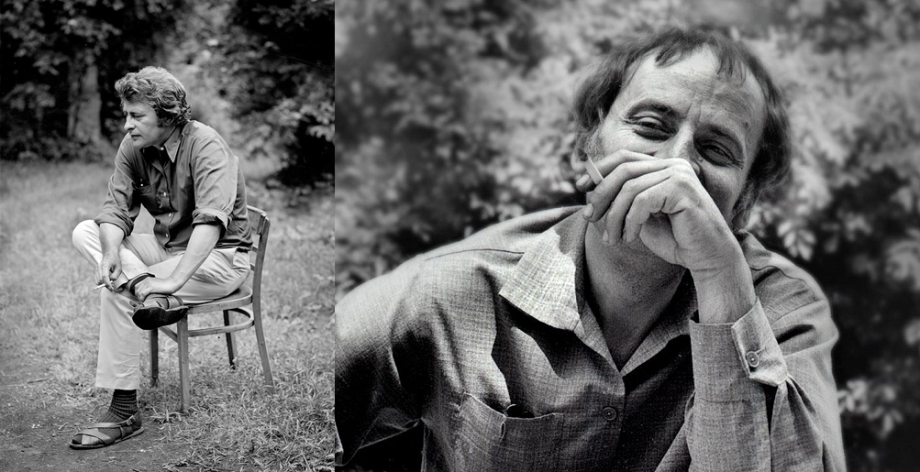

Břetislav Pojar and Miroslav Štěpánek, photographed by Ivan Vít in the garden of Čiklovka in 1974.

The joint screenings, in particular, arose from how the filmed footage had to be sent to the laboratories at Barrandov to be developed. Much trepidation and excitement surrounded these screenings, not least because there was no way for the animators and other staffers to preview how their work would turn out while it was being filmed, and it was here that certain shortcomings or mistakes in the course of filming came to light. As Jiří Barta, who directed his first films towards the end of the decade at Čiklovka, recalled,

The material was always taken out once in a while, it was, I don’t know, three or four days. And it was sent to the labs. Well, and after three days the call came…It was a suspenseful moment, because for one thing it might not have worked out as animation and for another it might not have worked out with the camera, well, and then there could be completely technical mistakes that we did not anticipate. The whole batch had to be reshot. Today you can see them immediately. […] Back then it was more of a surprise and everyone was nervous. When we were sitting, the call always resounded in the corridor and everyone gathered into the screening, because they wanted to see it. Not only those who worked directly on it, but also the people from the workshops, everyone, even the cleaner…That’s how the film was created.

And so we come to Břetislav Pojar’s next series, The Garden (Zahrada). In many ways, it could be considered Čiklovka’s flagship series. Befitting the studio’s new status, and no doubt in tribute to Pojar’s recently-deceased mentor and friend, it was based on a 1962 picture book by Jiří Trnka, who had a prolific side career as an illustrator. Just as Pojar developed his own distinctive vision as a filmmaker at Čiklovka, however, so too did the series go in a decidedly different direction from how Trnka might have adapted his book, with more of an emphasis on Pojar’s trademark humor than on Trnka’s lyricism. In a 2007 interview with Agáta Pilátová, Pojar explained why he chose to adapt The Garden in particular, and how he expanded upon the original (using the series’ first entry The Animal Lover as an example):

I first heard it read on the radio, I think by Karel Höger, and it interested me greatly. Then the book just came into my hands. But my film goes quite beyond Trnka, it couldn’t be any other way. There are many motifs in the text that I had to develop and solve in my own way. In literature you do it quite simply, the author writes: “The old man died and the garden became overgrown.” And that’s it. But I needed something to be left behind by the old man, especially the animals. This is also why this film is perhaps more visually complicated than some others.

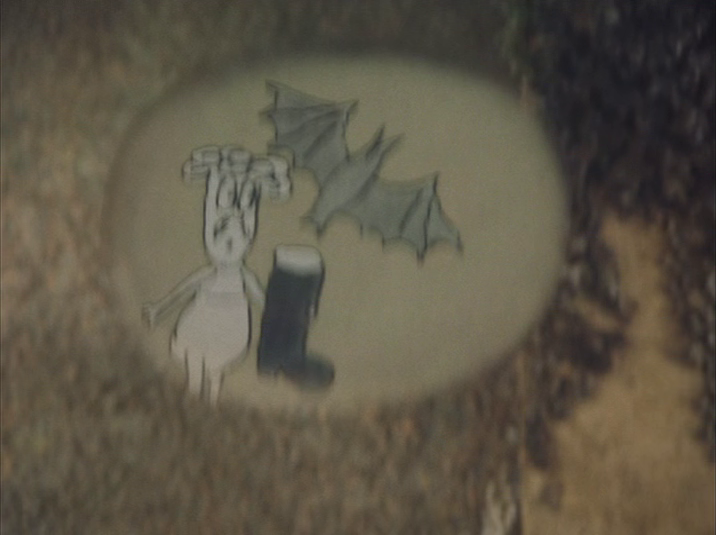

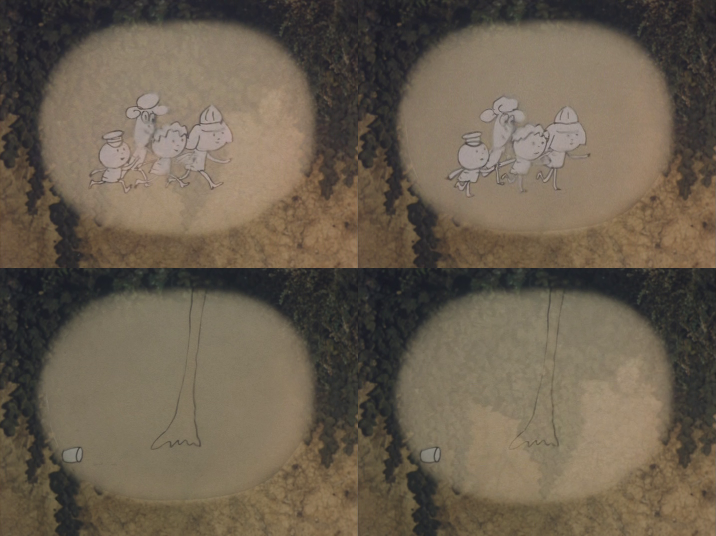

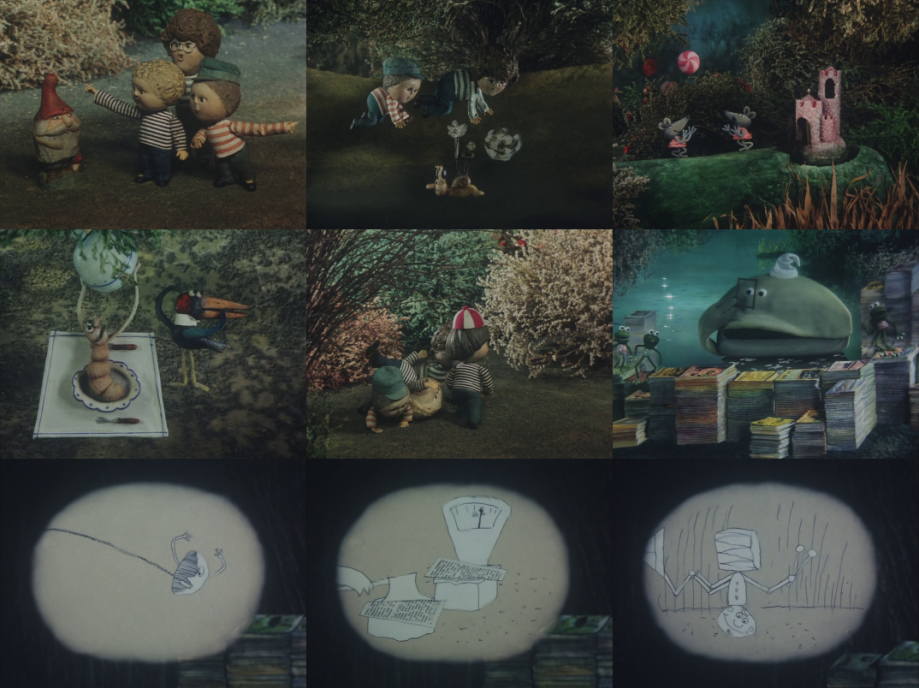

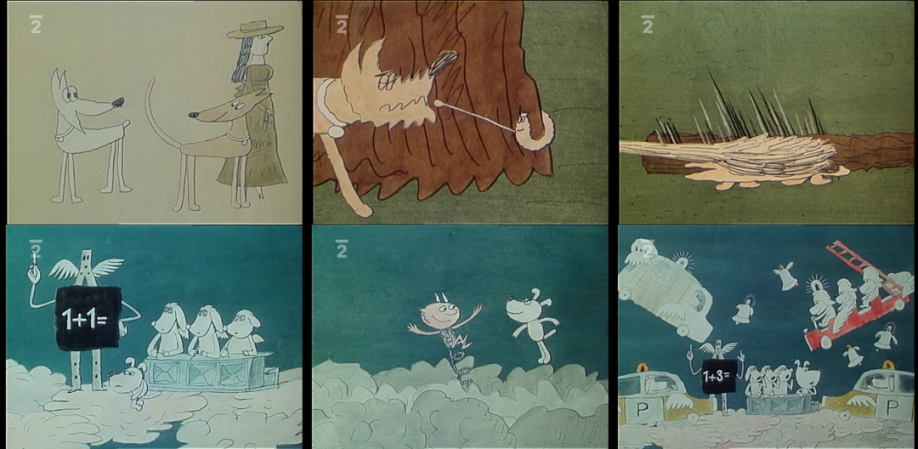

Trnka drew inspiration for the book from the beautiful garden in the villa of Turbová, where he and his family lived from 1939 to 1958; perhaps the series in turn echoes Čiklovka’s own romantic garden, with its extensive sculptural ruins amidst the decorative greenery. Its eclectic, oddball cast of characters, meanwhile, was a perfect opportunity to create and mix different kinds of puppets, in keeping with the experimentation with different materials that had taken place in Čiklovka’s 1960s films. Most notably, however, the series was an impeccable combination of the three forms of stop-motion animation that Pojar had excelled in: classical puppets inhabiting a three-dimensional space, semi-relief puppets on a flat plane, and cutouts. Each film regularly alternated between the former two depending on the needs of a given shot, while cutouts would be used to depict the lads’ bizarre thoughts and fantasies; clearly, as he himself discussed at length in his earlier interview With Head In the Clouds and Feet on the Ground, Pojar had discovered the benefits of combining these different techniques.

What is remarkable in this regard is that, when watching The Garden, one does not really notice that Pojar and his team are essentially switching between two different forms of stop-motion in every other scene or shot. It is a testament to Pojar’s intuition as a filmmaker that the use of either three-dimensional space or a flatter, two-dimensional plane for a given shot is simply what feels right for that particular shot, even in relation to the shots surrounding it, rather than being dictated purely by practical considerations like the presence of animals or above-ground characters. For that matter, designer Miroslav Štěpánek and the set builders at Čiklovka did a perfect job keeping the art direction consistent between the two different kinds of sets, such that the characters always seem to be inhabiting the same setting regardless of the different perspectives; the semi-relief versions of the sets, in particular, always consist of multiple layers of artistry, creating a sense of depth that hides the fact that the characters are being moved against a flat glass surface in these shots.

Of course, Štěpánek’s collaboration was invaluable in ensuring that the series would retain the beauty of Trnka’s original illustrations. While not a direct facsimile of Trnka’s artwork, Štěpánek’s rich art direction succeeds at creating a similarly enchanting, magical, densely-forested garden: it is filled with various kinds of intricately-sculpted trees and bushes—the abundant rose bushes, in particular, bring extra color and elegance—and its sense of mystique and wonder is furthered by the extensive shadows cast by the foliage, in tandem with the glimmers of sunlight that peek through (special credits must go to cameraman Vladimír Malík and his assistants in this regard). For that matter, even the less ambitious elements or settings, like the mossy, pebbly ground or the city in which the boys live, are simply staggering in their craftsmanship, with intricate details and textures that must have put the skills of Čiklovka’s preparation team to the test.

Where the series most deviates from the picture book artistically is in the character designs. Rather than trying to recreate Trnka’s very distinctive designs for the boys and the animals, Štěpánek and Pojar opted for a fun contrast in their own style. The four boys (reduced from five in the original book), in addition to being given their own personalities and looks to match, were crafted in a realistic style reminiscent of the characters in The Appletree Maiden; the animals, meanwhile, were designed in a stylized, cartoonish manner reminiscent of the second Bears series. The Tomcat, in particular, is anthropomorphized and animated in such a way that he could have been right out of the second Bears series, an impression furthered by how he is even voiced by František Filipovský.

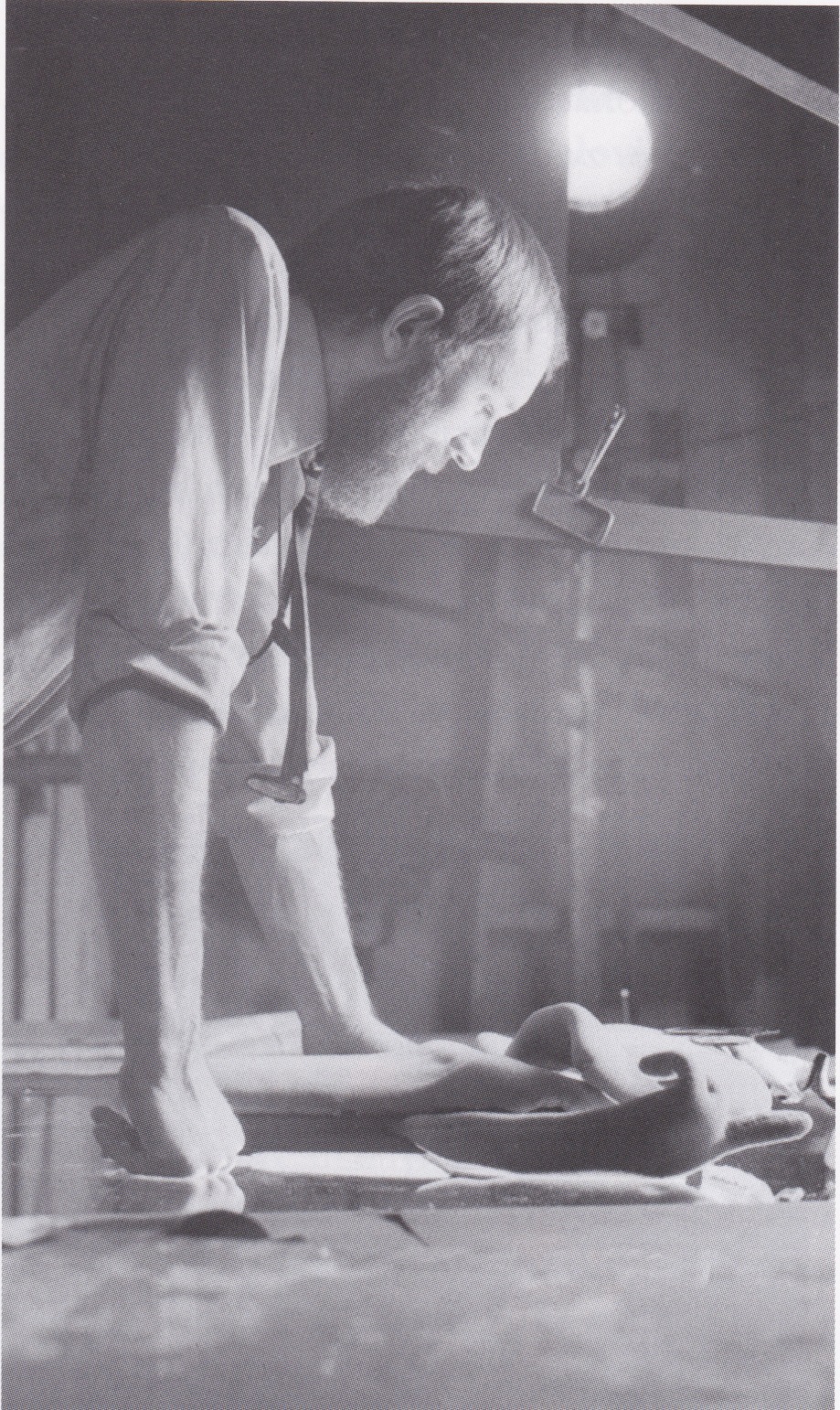

As usual, Pojar’s rich character acting, channeled by veteran animator Boris Masník and newcomer Jan Klos—in a nice division of labor, Masník animated most of the shots done in semi-relief form, where the most complicated elements like the animals were generally handled, while Klos was principally in charge of the scenes shot on three-dimensional sets with classical puppets—is what truly brings the series to life. As with the later Bears entries, the major presence of dialogue meant that the characters’ movements and lips had to be animated in sync with the pre-existing audio, and the sheer amount and variety of characters here only further complicated the process. (Here I remind you, of course, that Masník in particular was deaf-mute, and would have had to rely on his observation of Pojar and his rhythms as he literally acted out the scenes for Masník to figure out the timing of the lips and acting gestures.) It remains a testament to their incredible skills that the character animation turned out so well: the lip-sync is almost flawless, and so too do the emphatic gestures and movements perfectly match up with the dialogue. All these efforts—from Pojar, Masník and Klos, Štěpánek, Malík, the other assistants and builders and artists at Čiklovka—must be kept in mind, as we now delve into The Garden itself…

A photo of Boris Masník at work on The Appletree Maiden, just prior to The Garden. Photo taken by Ivan Vít.

The Animal Lover / Milovník zvířat (1974)

Right from when Jiří Kolafa’s catchy, old-timey theme song begins with a lone whistler almost calling for our attention, heard over the Trnka Studio logo emblazoned at the front—while variations of this logo had been used in films from Konvikt since the late 1940s, this was the first film from Čiklovka to feature the logo, and quite fittingly so—we know that we are in for a special time in the garden. The first entry in the series, The Animal Lover, serves as an introduction to how the garden came to be, and taken on its own, it is easily one of Pojar’s most charming and brilliantly-constructed films. It is the heartwarming but melancholic story of a kind, lonely old man who decides to adopt and raise some small animals, treating them with such love and affection that, over time, they grow bigger and bigger until they have transformed into something much greater than he could have ever imagined.

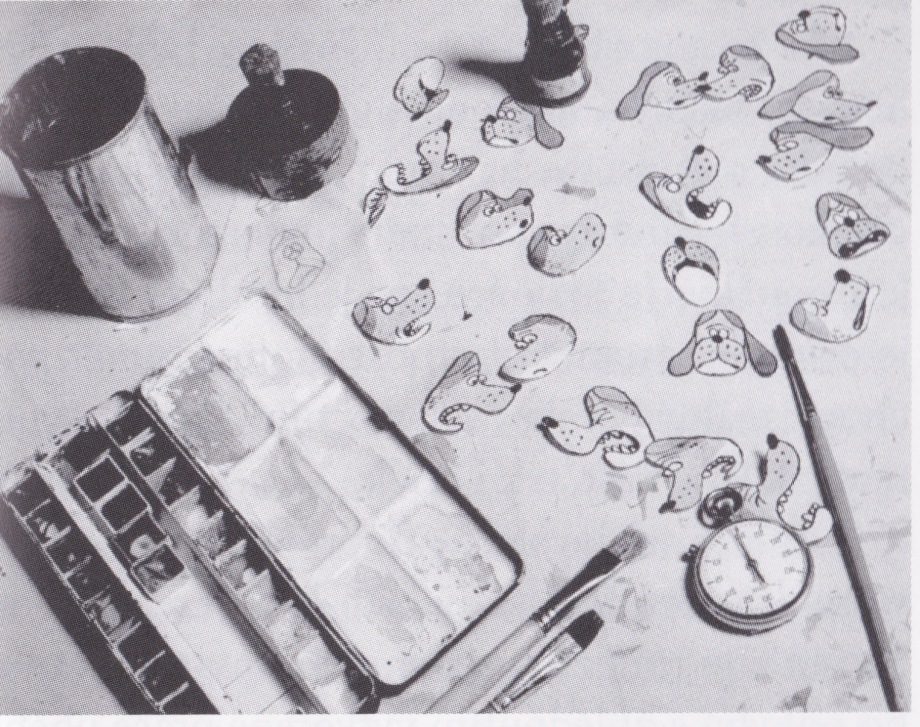

Unlike the rest of the series, The Animal Lover was crafted entirely in cutout animation. In stark contrast to the more minimal art direction of Pojar’s previous cutout-animated films, however, here he and designer Miroslav Štěpánek opted for a warm, painterly, storybook-like look, perfectly befitting the film’s quaint setting and story; its rich textures and colors extend even to the character cutouts themselves. Of course, as Jan Klos has described in detail, the production of a cutout film at Čiklovka was only slightly less strenuous than that of a puppet film—essentially, Pojar planned out all of the character acting in advance, and from there supervised the preparation of a cutout “actor’s kit” consisting of all the parts and joints and bodily conformations and such needed for the animators to actually “phase” the movements he demanded (I have combined two different explanations, one he gave to Veronika Hanáková in 2019 and another he gave to Marin Pažanin in 2020):

[The Animal Lover] was made by the so-called “Paper Method” – it is similar to a cartoon, but it uses the so-called “Actor’s Kit”, which was prepared perfectly and economically by Pojar and a team of girls from “preparation”. [They] contoured it, colored it…The actor’s kit on tracing paper was transferred to moistened, tight-fitting paper, which tightens up perfectly as it dries, two girls transfer the game and the actor’s kit to it – in some cases it was put straight into the car on the boards of the original designer, so that the original graphics really played. The individual phases [of the animation] are pressed onto the background by a large glass.

The old gentleman’s longing for companionship is clear from the first scene in the film, as he watches and contemplates his neighbors through their windows. The silhouetted, touching views of parental affection and kinship, as we see a father and his son playing trumpets together, a woman rocking her angelic baby, and other another woman playing with her child by lifting him up and down repeatedly, convince the gentleman that he ought to get a pet of some kind, rather than remaining all alone with his stone gnome who, in the end, is no substitute for real companionship. (Of course, he does continue to see it as something of an old friend, often elbowing or prodding it as though asking it to agree with his excitement at his new pets and even carrying it outside to do so once he begins spending most of his time there.)

That very night, he goes out and gets a little pet fish, and spends his days playing with it and feeding it regularly, always with the rhythmic declaration of “For Hansel, for Gretel, and for Pepíček” (who is the other two’s cousin in some versions of their story), before rocking it to sleep in its bowl. The rings that the gentleman blows from his cigar as he watches the fish, and the colorful bubbles that the fish blows as it sleeps, always rise high into the air together, serving as an oneiric, lyrical representation of the peaceful bliss that the two feel together.

The gentleman’s routines prove to be the perfect foundation to show how the fish changes and grows miraculously over time. Early on, the little fish is already quite interactive, giggling and looping around and leaping out of the water (even twirling in the air at times) as the gentleman suddenly rushes towards it with funny faces and then begins acting like a monster, albeit it can do little more to play with him than splash drops of water onto his head with its tail. Soon, the fish grows so big that the old gentleman must relocate it to a washbowl (in a show of how much he cares for the fish, he even checks the temperature of the water before putting the fish in), and we see even more clearly how the old gentleman still has a lot of liveliness left in him as he begins deftly popping out from various hiding places around the fish’s new home to surprise it with faces and even rapidly shakes off the water the fish splashes at him before taking on the form of a weird neckless freak and jumping towards the fish; the fish, in turn, has become something of a lively, energetic child as it now imbibes tons of water only to squirt it all out at the gentleman, who recoils exaggeratedly and arm-thrashingly as though it were his deadly weakness!

Later, as the fish grows big enough to occupy a bathtub, the gentleman must change his game accordingly, making a much bigger funny face by wearing a closed umbrella as a mustache and then using the umbrella as a spear and even taunting the fish with it; the fish, in turn splashes water so profusely that the gentleman must rapidly dart away each time to avoid getting wet, and when he hits upon the idea of opening the umbrella up as a shield against the water, the fish, in an astonishing show of its newfound strength, goes as far as to drag the gentleman into the bathtub by the tip of his umbrella! (We then see that the gentleman has to literally dump the water out of his sleeve and pant leg, and even forces the water in his head out through his right ear by giving himself a good smack on his left ear while jumping onto his right leg to shift the water accordingly.) Finally, the fish grows so big that the gentleman can no longer even play with it, and eventually must go as far as to wheelbarrow each “scoop” of food; Bohuš Záhorský’s warm narration does an especially good job here of conveying the gentleman’s exhaustion, as each recitation of “For Hansel, for Gretel, and for Pepíček” grows increasingly tired and heavy—and upon making the mistake of forgetting the food “for Pepíček”, the fish, now a whale and able to talk in a deep voice, punishes the man playfully with a single thrash of its tail that floods the whole house with bathwater!

Jiří Kolafa’s score as a whole is as playful as it is gentle and melancholy, with many recurring themes and leitmotifs. It is particularly effective at underscoring the growth that takes place in the animals over time, an astonishing feat when one realizes that (as animator Jan Klos recalls below) the music was not actually created before the animation, and accordingly depended on the rhythms which Klos and Boris Masník instilled in their work without aural accompaniment. For instance, when the gentleman begins interacting with the fish, we hear a jaunty, but rather docile flute theme, in keeping with how these two are still getting acquainted with each other and the fish itself is rather small; this is followed by a whimsical, fluttery flute-led theme as the two begin playing. Both themes are then performed at faster tempos after the fish grows the first time, with the second theme in particular being played more loudly and led by a flute at a lower octave in keeping with the fish’s growth and higher playfulness; later, when the fish has moved into the bathtub and begins playing there, the second theme is performed more slowly and at a lower key led by a weightier-sounding clarinet, in accordance with how heavy and mature the fish has become. One theme that initially remains constant is the beautiful, violin-led lullaby heard whenever the gentleman is rocking the fish to sleep; however, after the gentleman, surrounded by bathwater, realizes that the fish has become a whale far too big for him to deal with, we get a minimalistic, pensive-sounding, clarinet-led variation of the lullaby punctuated by a marimba and some heavy bass plucks (and the perfectly-timed ringing of a triangle when the massive bubble blown by the whale pops with such strength that it rocks the gentleman on his wheelbarrow), expressing how the gentleman must be feeling as he has reached quite the dilemma.

Similar, but equally exciting and endearing patterns—growth-wise and musically—are followed when the gentleman decides to get some puppies. When the little puppies first emerge from their doghouse, they practically roll out of the entrance in their lack of control over their delicate limbs, which at any rate aren’t quite strong yet, as evidenced by how one of them falls over as it tries standing on its hind legs for the gentleman; when they try fetching a little flower that the gentleman has thrown (again, one of them practically rolls its way over), they are frightened away by a butterfly, and as they try to cuddle up to the gentleman, he has to pick them up so they can rest on his lap. Their bouncy theme, which should otherwise be frisky, is accordingly played at a slow tempo, sounding rather curious and uncertain. Soon enough, the puppies grow into energetic, excited dogs who barely fit into their house as they nearly break off a loose board over their entrance while rushing out, and who are now able to jump on their hind legs for the gentleman and fetch a stick on their own, even wrestling energetically over the stick as they practically spin each other around and carry each other along on it; it takes a larger amount of food to create a scent strong enough to attract them, and they can now hop up onto the gentleman’s bench on their own to rest in his lap. Accordingly, their theme becomes much faster and more playful, led by trumpets.

Not long after, though, the dogs grow large enough that they outright break their house into pieces as they try to leave it, and the gentleman, after nearly falling over from their sheer weight as they lean on him to lick him, has to throw almost a log for them to fetch and wrestle over; in addition to an even larger amount of required food, the two dogs also end up breaking the gentleman’s bench as they try to hop up to sleep in his lap. In accordance with their weightier, largely-on-twos animation, the music is slower and heavier, with a more pronounced tuba. Eventually, they become full-blown dog-eared elephants who “bark” through their trunks, whose excited steps thunder with such force as to bounce the man off the ground and reduce the even-larger doghouse to shambles, and whose bringing of a tree as a “stick” causes the gentleman to faint, such that they have to wake him up; the melody is reduced to a lumbering, brass-dominated shell of its former self! Of course, what remains constant is the gentleman’s love for his animals, as another beautiful string theme always plays, without any change, every time the dogs rest in his lap; at the same time, though, it should be noted that the gentleman is no longer actually playing with his dogs like he did with the fish—a subtle but foreboding sign of how his old age is more and more taking its toll on his strength…

At last, the gentleman obtains a little kitten. By now, he is significantly weakened and all but sedentary, as he feeds the kitten directly from a bottle of milk while seated on his bench; the wistful lullaby heard here will henceforth be used throughout the series, as a recurring leitmotif for the garden as a whole. It is at this point, before the kitten has even grown into an ordinary cat, that death strikes—the smoke rings indicating that the man was still alive and breathing, and which the kitten had begun playing with, suddenly come to a halt, and the bottle of milk collapses onto the kitten’s basket and onto the ground, followed by the cigar itself as it almost floats solemnly to the ground, letting out one final breath of smoke. Now deprived of the old gentleman’s nurturing love, the kitten will not be able to grow into a Barbary lion—and in a sad example of how people in this world, cynically enough, do not care much about a single old gentleman’s death as long as they can profit from it, the kitten is then rolled from its basket and the bench itself by a jerk who takes most of the gentleman’s and animals’ belongings away, even as a bell is heard repeatedly tolling to signal the gentleman’s death. The animals can only watch as they are buried in time, ignored even by the birds flying through the air nonchalantly; Vladimír Malík’s camerawork here is skillful, as layers upon layers of flora grow and gradually cover the garden up, and the house in turn is obscured by the literal rise of new buildings in the increasingly modernizing city.

As cruel as it is, life continues to go on as usual even after someone beloved has died, and the old man who loved his animals is no exception. Per the narration, these days the garden is supposedly frequented only by dogs who go there for drinking parties, and Pojar, as expected, portrays this fact comically: in a sequence very loosely animated by Jan Klos, two (literal!) party animals stumble drunkenly through the streets in the night, heckling the sleeping townspeople with their noisy bark-singing and ultimately causing a shipload of objects to be thrown at them (the inaugural bucket and boot, in particular, are then used very practically by the dogs as protective headgear). Cleverly, though, Pojar then sets this relatable scenario of animal hatred up as a contrast with the deceased animal lover’s kindness; even at this moment, up in the heavens, his spirit is feeding clouds, turning them into larger, fully-animated cloud animals.

This lovely final scene is accompanied by a music box-like rendition of the old gentleman’s theme, which makes way for a beautiful flute coda. A similar rendition of the theme had already opened the story, segueing into an affectionate-sounding trumpet rearrangement of the last few bars or so (sounding quite similar to the whistling at the very beginning of the film!) as we see the father and son playing trumpets (and continuing appropriately into the scenes of parental love afterwards), and the theme itself had reoccurred at certain transitional points in the film: a slow, solemn, trumpet-led version played as the gentleman said farewell to his whale, and a faster, brighter-sounding version was heard as the gentleman left the elephants to play on their own in the garden.

To close, this film is one of Pojar’s most heartfelt creations, with moments of fine visual poetry and genuine emotion, and it works wonderfully as a charming stand-alone entry in the Garden series. It is essentially a touching meditation on the passage of time—how quickly and unbelievably, it seems, we grow from infancy to adulthood, and yet also how much we can accomplish even in such a short span of time as our final months of life. As noted above, the repetition of the old gentleman’s routines is a perfect way of illustrating just how dramatically and beautifully his pets—and by extension, our own children and pets—change over time, from the delicateness of their infancy, to the energy and friskiness of their childhood, and ultimately to the unbelievable strength and power of their adulthood. In that regard, it is also a marvelous illustration of the wondrous things love can do: it is simply heartening to watch the man care for his animals like his own children, as he gradually increases their food supply, enlarges their living quarters, and spends time with them until, one day, they have miraculously grown into truly great beings. While he must set them free in the outside world (that is, his new garden), he still helps them out where possible, as evidenced by how he excavates a lake for his whale, subscribes her to several magazines, and even uses a crane lift to transport her, and later has a gazebo with circus equipment built for his elephants.

With that, here are Jan Klos’s reminisces of The Animal Lover, and animating the scene towards the end with the drunk dogs, to Marin Pažanin:

The Animal Lover moved me right to tears. If it weren’t for the situation that Krátký Film wanted to produce quickly and cheaply, so that there was no money for good sound engineering (sound effects and music), one could speak of a nice professional film. I already phased there as a “collaborator” recognized by Pojar (learned to use simple and primitive phases as I went along) but I don’t like to remember the “big responsibility” when I had to phase the end of the film for the ill Boris [Masník] – how drunk dogs go through the city – there was no music, no singing – the city was supposed to go out, and it couldn’t be made in “cutouts” – it had to suffice in 1 day, nerves on the march – SO: I actually spoiled Pojar’s impression at the end of the film.

Naturally, this was not the only film Masník animated on in 1974: he was also the main animator of this year’s two hunting cartoons by Josef Kluge and František Skála, Pozor, medvěd! and Na posedu, neither of which are particularly good shorts. To be sure, Pozor, medvěd! does have eminently satisfying character animation throughout (I do wonder if Masník animated the whole short himself or if Jan Klos actually helped him out here as well—sadly, until a version with full credits surfaces, we may never know for sure), even if the gags involving the pursuit of a mischievous bear who turns out to be part of a circus are a little too fatuous and lowbrow. Na posedu, meanwhile, is even more insufferable, with the remarkably poor execution of some sequences (the second animator here was Břetislav Dvořák, who was otherwise busy churning out Kluge’s Mikeš shorts at the time) adding to the annoyance and unlikability of the story of a guardian angel who fails to keep the hunter from getting drunk with calamitous results; it culminates in a truly lousy ending in which everyone is brought to tears in a mock-funeral for the now-wingless angel. For that matter, this would not be the first time that Masník fell ill during the production of the Garden series; to this day, it is regrettable that he was stretched far too thin in Čiklovka’s later years, with a corresponding toll on his health and—as we shall see—on the quality of his animation as well.

Various freshly-painted cutouts of the dog from Josef Kluge’s hunting cartoons, designed by František Skála. Photo from the book Zlatý věk české loutkové animace, provided by Marin Pažanin.

Of That Great Fog / O té velké mlze (1975)

We now enter the series proper as the story of the mysterious garden fast-forwards to the present day, with even the opening theme song being updated to a catchier, more percussive and “modern”-sounding rendition. In this re-introductory entry, in which four lads who get lost in the fog on their way to school wind up rediscovering the old garden, Pojar and designer Miroslav Štěpánek create a small world of interesting contrasts and several unique characters: there is no mistaking the realistically-designed humans for the cartoonish animals, or the four lads for each other, or—perhaps most importantly—the cold, foggy city, with its panelák buildings and merciless punctuality, for the exquisite, enchanted garden, where it seems life is carefree and time has stood still.

Vladimír Malík’s camerawork shines right from the start, in the opening shots of the lads walking through the fog on their way to school. In both the semi-relief shots of the lads walking along and the impressive three-dimensional shots of the barely-visible streetlights moving past them, the fog effects appear to have been created with a combination of special lighting (which appears to have been fixed in place with the camera, as in some three-dimensional shots the fog-like glare remains constant even as the camera moves forth) and a scrolling glass layer with thinly-painted fog of some kind; it would not have been possible to actually control and animate the fog moving past the lads frame-by-frame otherwise. Jiří Kolafa’s music here, consisting of a sporadic, suspenseful rendition of what will prove to be the lads’ marching-on theme performed mostly by alternating harmonica and clarinet, adds to a certain wistful sense of mysteriousness as the boys make their way through the fog, which is thick and obscuring enough that, when the lads suddenly see the old house with the garden in the distance, their memorable first impression of it is of a spooky, ruined fortress of some kind—a fascinating destination for this quartet of young adventurers, as a slow, ominous clarinet version of the leitmotif whistled at the very beginning of each film in the series is added to the music.

Upon arriving at the gate, we see that the lads (voiced by actresses Pavlína Filipovská, Iva Janžurová, Jiřina Jirásková, and Růžena Merunková) differ not only in looks, but also in their personalities and their interactions with each other, and they maintain an engaging chemistry as they try to open the locked gate with various objects, constantly reassuring and chiding each other but also working together with playful relish when the opportunity arises. It is easy to tell which one is the leader, frustrated whenever things don’t go his way and always having to rely on the others for ideas and help; the nerdy one, continually hesitant and nervous about taking risks; the more normal one, who mostly seems to tag along but occasionally has ideas and thoughts of his own; and finally the smallest one, who often seems to get the worst of a situation, and who is extremely possessive to boot, crying when he loses his money-box key to the gate and loftily referring to his harmonica as a “steamer”. Of course, they do not strictly adhere to these main personality traits either, making them all the more interesting as characters: it is the nerdy lad who comes up with the inspired but failed idea of trying to clog the lock up with various objects, and the smallest one, when pressured, can easily be the most bold and courageous, to the point where he personally marches over to the gate to sacrifice his treasured harmonica to the keyhole (which is what finally opens the gate) rather than letting the others take it and do it for him. (In a nice touch, this scene is accompanied by a solo-harmonica march.) For that matter, even with their semi-realistic designs and impeccably naturalistic character acting, the lads sometimes engage in cartoonish movements, like how the leader’s head bounces squashy-stretchily in surprise at the little key falling into the gate or how they stretch their arms or legs out at times to grab things.

The lads’ initial awe at the abandoned but sunlit garden, shielded from the fog outside, is well-conveyed by a pan through all the thick, dense shrubs and rose bushes with overgrown woods in the background, accompanied by a wondrous-sounding violin-led version of the garden’s leitmotif. But after wandering in too far after some butterflies, the lads are frightened off by a screeching, hissing monster of some kind, their heads briefly bouncing squashy-stretchily in shock and the yellow-haired lad even tripping over the smallest lad in his haste to get away! (With regards to the heads, I have to wonder how Miroslav Štěpánek felt about having to sculpt these squashed versions of the lads’ heads; per Pojar and then-costume designer Alena Meissnerová, as designer he was responsible for sculpting the heads of the final puppets himself even as Čiklovka’s preparation team did the rest.)

The monster turns out to be a massive, disguised Tomcat, grown up from the kitten who had been abandoned after the old gentleman’s death; perhaps the garden itself has some magic that allowed him to grow as big as he is. No doubt owing to his experience with the man who took everything away, the Tomcat is quite misanthropic, clearly relishing in how he scared the lads; even without taking his past into account, however, his eccentric old man-like mischievousness makes him impossible to truly dislike, especially with his very lively mockery of the lads (animated by Boris Masník who was almost exclusively responsible for the Tomcat), with its finger-pointing, nodding, and mattress-bouncing in tandem with his elderly laughing. Of course, the Tomcat is quite fine with mockery as long as he himself is not the target: his mischievousness quickly turns to violent crankiness after the smallest lad, in another show of his true boldness, jumps right up to him and calls him an old broom, and the ensuing mayhem in which he aggressively throws objects one-by-one at each of the insulting lads with his noodly arms (with each lad managing to dodge behind the wall just in time), uses his tail as a slingshot against the smallest lad, and finally lunges right into the door as soon as it is slammed shut is a particularly excellent example of Pojar’s knack for comic timing!

There are some intriguing quirks and errors, however, within this first sequence in the garden, making clear that the staffers were still getting used to working with this very elaborate set. The grasses that surround the garden entrance often shift and move subtly, as though Jan Klos could not avoid accidentally touching them while animating the puppets of the lads; for that matter, the tree branch above the mocking Tomcat is shifted upward during the second time he laughs at the lads, right before the shot zooms out slightly (perhaps the shift was necessary to hide some kind of flaw or cutoff in the branch?). Most notably, the first two shots of the lads insulting the Tomcat one-by-one and dodging his projectiles suffer from a strange lighting issue, such that a blue light is visible at the top-right corner of the screen; it noticeably disappears each time one of the Tomcat’s projectiles enters the screen at that very spot, only to reappear or flicker back into view, and the shots afterwards remedy it by readjusting the camera’s position outright. Of course, the fact that these errors exist in the final film is a valuable reminder that, due to both technological limitations and the budgetary and time restrictions dictated by the production plan, these films often had to be shot “blindly” and on the first try, with no real chance of previewing how the animation or camerawork would turn out or correcting any potential mistakes in them afterwards; it remains a testament to the abilities of Pojar and his team that they came out as polished-looking as they did.

As the lads flee back to the city with the cranky Tomcat’s insults continuing to echo out from the garden, they are seen by the four wrinkly elephants (multiplied from the original two that the gentleman had, and voiced by Vlastimil Brodský, Lubomír Lipský, Zdeněk Řehoř, and Stella Zázvorková). Realizing that they are almost late to school after all of this dawdling, the lads begin a mad, futile rush to make it in time (in their hurry, most of them unthinkingly start off in the opposite direction, with the leader having to yell after them and even bang on his head to let them know how stupid they are)—and it is then that the elephants, retaining their endearing friskiness and eagerness to please from when they were dogs in The Animal Lover even as their very stomps send the lads jumping along the sidewalk, begin to chase after the lads, believing that they are playing tag. Their earnest desire to play is met only with the lads’ hurried grief over their lateness to school, and their sincere remorse over the mistake is such that they all begin sobbing large tears—which, in a clever sight gag, nearly drown a street sweeper who has jumped into his bin out of fear at the oncoming stampede! (Some more shooting errors here, incidentally: the whole scene of the lads bewailing their lateness to the elephants has some noticeable fluctuations in brightness, and in one shot, the background scrolling behind the lads abruptly shifts downward.)

After hearing that the lads’ classroom is on a higher floor, the smallest elephant—smashing right into the others who, initially at a loss, have come to a halt—realizes that the elephants can help out with the lads’ situation, and with that, the elephants speed the lads along by letting them ride an elephant train: in an example of them (and Pojar) going the extra creative mile, the front two elephants sound it off with a fanfare, then (after bringing the boys on board) develop a train whistle, wheels, and smoke-blower, with Jiří Kolafa scoring the noise excellently via a ragtime soundtrack punctuated by elephant-like horns! Naturally, they continue to terrorize the city at this time, as they scare others into running away on stilts (you have to love how this man’s hat flies up and twirls in shock at the sight of the elephant train, or how he just happened to be carrying some stilts for whatever reason) or climbing up clocks to get out of the way—and then they pass behind some scaffolding, during which the lighting of the scene noticeably gets darker. According to Jan Klos, this particular shot and its execution was another result of animator Boris Masník’s poor health and his need for recovery during the production:

The elephants take the boys to school. They run through the city – a long job with each phase – Boris has paid the spa for three weeks, he has to leave tomorrow – we found a kind of “scaffolding” in the studio – as if the elephants are running behind the scaffolding. And when they ran behind it, we turned off everything, turned off the camera, and after three weeks of Boris’s treatment, we continued to phase the run – in the middle of one scene. You can see it there, how the scaffolding subtly changes the brightness. It’s an accurate picture of work in Krátký Film Prague, where the plan orders a scene to be shot in 1 day, and when you start shooting it, it takes 3 days from morning to evening.

In effect, the scaffolding was a convenient way to hide any obvious changes or flubs that would have been noticeable after Masník had not used the puppets for weeks. It is a good example of Pojar’s imaginative practicality as a director—aside from allowing Masník to rest and pick the work back up later without anyone noticing there had been a break in the middle of shooting, the scaffolding also works as a sort of extra atmospheric detail, illustrating the continuous urban development of this modern city.

This then leads to another funny gag, in which the elephants arrive at an intersection—scaring the traffic cop, who in his panic inadvertently orders a woman to stop right in the elephants’ path, in turn causing the (bare-legged!) woman to jump onto her car and tremble frightfully at the sight of the oncoming train before the cop, realizing his mistake, manages to kick the car away and grab the woman just in time! Per Klos, this was one of a number of special semi-relief shots in which he and Masník actually worked together: Masník animated the cop, while Klos animated the woman and the elephants, and the rapidly-trembling woman in particular is a brilliant early example of Klos’s exuberance, which would become even more pronounced by the end of the decade.

By now, all of the city’s clocks are striking eight, and we see the strict punctuality of the schoolhouse as its doors close almost immediately afterwards. It is then that the lads and the elephants arrive to find that the window of their classroom is luckily still open—and in a combination of brilliant camerawork from Vladimír Malík and skillful editing from Jitka Kavalierová, we rapidly truck into the semi-relief schoolhouse’s window to enter the three-dimensionally-depicted classroom (a seamless transition between the two different forms of stop-motion!), where the lads’ math teacher (almost certainly voiced by narrator Bohuš Záhorský) inadvertently buys extra time for them by believing they are once again playing a prank in which they hide beneath their bench to fool him into thinking they’re not there! (Quite a tangled web of trickery—of course, one has to wonder what mischief these lads are normally up to in school, that the teacher would be convinced they’re pulling something like that yet again.) As the teacher counts to three by literally adding 1 each time, the elephants manage to scoop the lads into an inverted umbrella—allowing them to be dumped in all at once, right on time and in perfect keeping with what the teacher expected! (I like the extra little gag of the leader and the smallest lad swiping their hats right off in keeping with proper indoor manners, preventing the teacher from realizing that they’ve just now entered.)

A cute running gag throughout the film is how the smallest lad’s pants keep falling off from time to time, after the other lads over-stretch them in their attempt to literally shake him down and dump his harmonica out to open the gate. It culminates at the end, when, having made it to class, he sneaks over to the window to wave the elephants goodbye, only for the pants to be left there as he returns to his seat; alerted by the other lads (the nerdy one even points at his own head repeatedly to convey how dumb the smallest one is), he jumps back into his seat before the teacher can notice and then extends his leg all the way out to swipe the pants back! A swell, cartoony way to end this lovely introduction to our many new characters, as the boys begin their math exercises—and elbow each other triumphantly at how they’ve managed to experience this wondrous morning adventure without getting in trouble. Naturally, they intend to return to the garden soon…

Aside from Of That Great Fog and the Mikeš shorts, the only other film to be produced at Čiklovka in 1975 was Carnivorous Julie (Masožravá Julie), directed and designed by a rather obscure figure named Pavlína “Pavla” Řezníčková. It is essentially a charmingly grotesque illustrated adaptation of an amusing tale by the great writer Miloš Macourek, about a carnivorous flower who causes an uproar in the city with her appetite, with sparse touches of cutout animation. The film is mainly notable as another example of how staffers from Konvikt (the actual Trnka Studio) began helping out at Čiklovka now that it was officially a branch of the Trnka Studio: aside from Čiklovka regulars Břetislav Dvořák and Jan Klos, the third credited animator is Konvikt’s Karel Chocholín (who would later animate the majority of the classic …a je to! series starring Pat and Mat), and the editor is Trnka veteran Helena Lebdušková, in the first of only two films she edited for Čiklovka after 1968.

As for Řezníčková herself, she was born in Prague on January 6, 1944, and studied at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, where she was a student of Adolf Hoffmeister, from 1963 to 1969, before becoming a professional artist in 1970. She had already designed and directed another film based on a Miloš Macourek story in 1973, Big-Eared Cecilia (Ušatá Cecilie), at the studio Bratři v triku; this was also mostly based on her illustrations, with bits of animation here and there drawn by Jaroslav Doubrava, one of the studio’s top veteran animators. (Doubrava, in fact, was already partnering with Macourek and designer Adolf Born by this time, serving as the lead animator on various satirical films like What If… (Co kdyby…) and From the Life of Birds (Ze života ptáků) and then the classic Mach and Šebestová shorts which the trio directed together.) After marrying a Spanish filmmaker, she immigrated to Spain in 1976, becoming a picture book illustrator of some renown; during this time, she managed to design two Slovak animated films, Ako sa Mišo oženil (1978) and Obyčajný príbeh (1982), both of which were directed by Zlatica Vejchodská. In 1990, Řezníčková became Czechoslovakia’s only post-Communist ambassador to Spain, from there continuing as the new Czech Republic’s first ambassador there (she served until February 1996); she eventually resumed working as an artist, with one of her more recent works being the 2007 picture book “O Dorotce a psovi Ukšukovi” (Of Dorothy and the Dog Ukšuk), written by Viola Fischerová.

Additionally, from this point on, Marta Šíchová is replaced as Čiklovka’s producer by Tomáš Formáček; like Šíchová, Formáček split his time between Čiklovka and Konvikt. The change seems to have taken place fairly early in 1975: the first Mikeš short produced that year, Překvapení v Hrusicích, still credits Šíchová as producer, while the rest of that year’s Mikeš entries (Mikeš hrdina, Tajemný kocourek, Jak se Herodes uzdravil), along with Of That Great Fog and Carnivorous Julie, credit Formáček. Lastly, animator Kristina Tichá, whom we had last seen taking time off before the end of the second Bears series, and who was now married with the surname Batystová, had returned to working at Čiklovka by this time, as she is credited as an assistant here and in the next entry. She would only become a full-fledged animator again in 1978, and even then only for cutout-animated films; as stated previously, she would remain a cutout animator for the rest of her career.

How to Catch a Tiger / Jak ulovit tygra (1976)